A response to Dana Suleiman’s “Ana Mish Mastoora” and the comments on that article

By Siwar Masannat

When I read Dana Suleiman’s article on 7iber yesterday, I felt she expressed something that often bothers me as a Jordanian woman and a feminist. She articulated a subtle, yet I think, very important issue that is by no means trivial but indicative of the type of mentality and perception that is the root of bigger issues concerning women in Jordan and the Middle East. Some of the comments that followed the article deeply enraged me. Some people expressed outrage to Dana’s ideas, some indicated their opposition to her article and Feminism at large, but worst of all, I think, is that some trivialized this problem and denied the importance of Feminist writing in a world of political upheaval, poverty, and transgressions of human rights. I find this not only “democratically” problematic, but also an inherent manifestation of our society’s sexism. Why is it that Feminist expression is often considered devoid of urgency? Why is it never “the right time” to express discontent with, or opposition to, traditional values or widespread social behaviors that impact women? Why is Feminism, and Feminist expression, often perceived as unnecessary?

As a feminist, I never think of Feminism’s agenda as promoting “enmity” between the genders, but rather revealing the discrepancies, especially in our conservative society, between the rights of these two genders. Feminism is not redundant as long as there are women who do not enjoy equal opportunity to men in education or work (whether that is the result of patriarchy or sexist laws or regulations). Feminism is not redundant as long as physical and sexual assault happen to women. Feminism is not redundant as long as honor crimes still occur and go lightly punished.

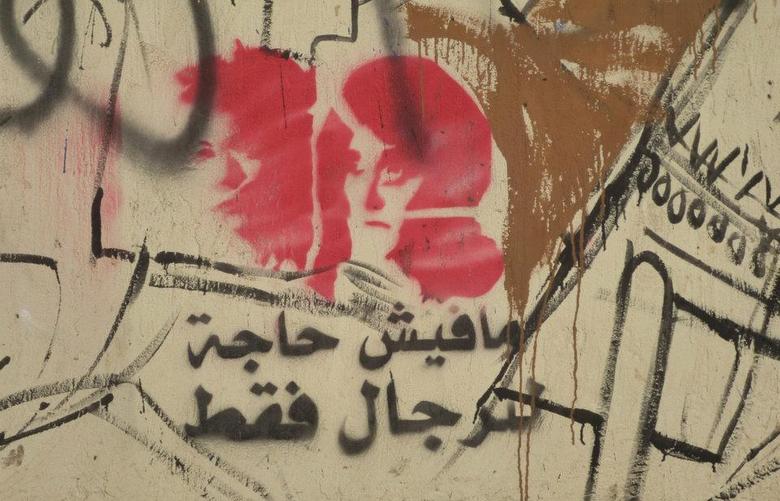

I think the importance of Dana’s article is that it shows how the language we use in our everyday lives could be deeply offensive to women. The importance of that is the link between the sexist origin of these subtle expressions and other behaviors less subtly violent towards women. By classifying women into categories of “honorable” or “dishonorable” in our everyday lives— even if subconsciously, even if spontaneously as a common Arabic expression—and allowing men to be the arbiters—even women’s saviors from one of these categories— we are allowing the logic that supports men’s hegemony over women to remain normalized in our society. We are not protesting the logic supporting honor crimes, we are allowing men’s control over women that may translate to physical assault (within and outside of familial and marital relationships) or sexual assault (again within and outside familial and marital relationships), and we are supporting sexual inequalities that exist between genders.

Furthermore, the perception that a woman is not “mastoora” if she is unmarried is sexist and dangerous, because it implies that men are responsible for straightening women’s behavior. The notion that men are the moral “keepers” of women normalizes women’s dependence on men and disempowers them. If women are not allowed their independence, then they are less effective members of society. What is a woman to do if she happens to be robbed of the “security” provided to her by “her men”? How will a woman be able to survive a sudden absence of a husband, or father, or brother, if society never allows her to be independent? Are we a good society if we do not ensure that both genders are equally treated and afforded equal chances to be self-sufficient? Feminism, in activism and in written or artistic expression, is what can help women overcome sexism and discrimination, is what can help them achieve independence. It is necessary and should not be allowed to exist conditionally.

Finally, women’s independence should not be offensive to men; it should not threaten any real man’s sense of masculinity. Real masculinity is not about opening the door and being responsible for helpless females. Real masculinity is being capable of respect without disempowering or dismissing a woman. Real masculinity is about feeling secure enough in one’s selfhood that repressing the other gender is never a definition of oneself.