(This piece is republished from Mada Masr)

By Naira Antoun

“I am not interested in electoral programs,” declares Mazen Khaled, a 23-year old volunteer in the Kammel Gemeelak (Fulfil Your Promise) campaign. “It’s the CV, what has the person done.”

It has become a truism to say that many Egyptians would struggle to remember the name of their interim president, Adly Mansour. For many, Field Marshal Abdel Fattah al-Sisi, who has steered the course of the previous period, has already proven himself a worthy president.

Now that Sisi has officially announced his bid for the presidency, people like Khaled will be busy campaigning, either through “Kammel Gemeelak“ or other more official campaigns.

Though this campaign preceded Sisi’s official announcement and resignation from the Armed Forces to pursue a career in politics, and though it is centered on Sisi’s presidency being the normal extension of his ousting of his predecessor (hence the name of the campaign), the people of “Kammel Gemeelak” see elections and campaigning as important channels.

“We don’t want Sisi to be the only candidate,” says Rifai Nasrallah, the founder and chairperson of the campaign. “That would reinforce the view that it is a military coup. We want democratic practice and this campaign is part of that.”

But for those “Kammel Gemeelak” campaigners Mada Masr spoke to, defending Sisi’s presidency is less about a new promise and more about restoring three tumultuous years of revolutionary unsettlement.

“I don’t care about his proposals for the economy. When security and stability are achieved, then the economy will grow,” Khaled says.

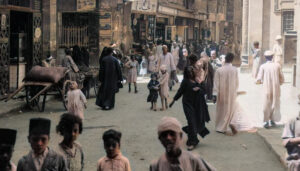

Insecurity has been a problem in Egypt, Khaled believes, since January 28, 2011, dubbed the Friday of Anger, when police stations were attacked across the country.

“We were in popular committees, protecting our homes,” he says. “Since then, no one has been able to sleep.”

Mahmoud Ali, with whom Khaled is tying laminated pictures of Sisi with ribbon while waiting for a Kamel Gemeelak press conference at an upmarket hotel in Giza to begin, also has an ambivalent relationship with the January 25 revolution.

Unlike Khaled, Ali went to the streets on January 25, and then voted in the presidential elections for Ahmed Shafiq in both the first round and in the runoff against Brotherhood candidate Mohamed Morsi. As a former aviation minister and former President Hosni Mubarak’s last prime minister, Shafiq was the candidate least associated with change.

After the fall of Mubarak on February 11, 2011, the next time that Ali joined a demonstration was June 30, 2013, in the protests against Morsi’s rule. He had not taken part in any political campaign before his involvement with Kammel Gemeelak.

When they are done with the photos of Sisi making a salute, tied up with ribbon ready for people to wear around their necks, Ali, Khaled and the other young men appear a little restless, unsure what to do with themselves.

There is some uncertainty as half the typed signs indicating who will speak are replaced by handwritten ones. When large banners arrive, probably about an hour after the press conference is meant to begin, they busy themselves hanging them up behind the table set up for six speakers and around the conference hall that is gradually filling up. Finally, as the speakers arrive, the young men look visibly more relaxed.

A number of the banners declare youth support for the field marshal.

Apart from expressing support for Sisi and what he represents broadly, the campaign also has an eye on more skeptical audiences, both in Egypt and abroad. For one, there is the question of youth support.

The campaign is organizing a youth football cup. As he announced it at the press conference, Nasrallah said it would be a “message to the world that the youth stand behind Sisi and tens of thousands will support him in the elections.”

Since the uprising of January 2011 was widely dubbed a youth revolution, young people are seen as carrying a certain legitimacy. The sight of queues of older people voting in the constitutional referendum last month evoked handwringing about the absence of the youth amid celebration of the referendum as a kind of wedding. Less about the constitutional draft ostensibly being voted on, the vote was more a poll on the past six months and the direction in which the country is being taken — a question that most young people appear to have refrained from answering.

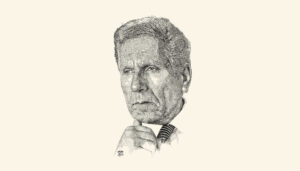

But while the campaign has an eye on the youth as an index to the future, it also has an eye on the past. It is less the image of Sisi alongside Gamal Abdel Nasser that has become associated with the campaign, but Sisi flanked by both of Egypt’s presidents who preceded Mubarak — Nasser and Anwar Sadat.

The image that has become associated with the campaign is of Sisi flanked by both of Egypt’s presidents who preceded Mubarak — Nasser and Anwar Sadat.

It is a telling image. It projects the future by recalling the past — bypassing any risky references to Mubarak. It is reflected in the rhetoric both of the field marshal himself and the campaign — one that sees Egypt as a glorious nation, with a long and great history, that will take its (rightful) place leading the Arab world.

“For 50 years we haven’t seen a figure like this,” Nasrallah says. “Sisi combines the leadership of Nasser and wisdom of Sadat.”

“While Nasser was enthusiastic and took revolutionary decisions, Sadat had political acumen and took wise decisions. Egypt needs both,” he says.

It is from this somewhat unlikely mix that Nasrallah projects the nature of a Sisi presidency.

“He will lead the Arab world. He will stand up to America and all those states plotting against Egypt, but he won’t go and make a speech insulting America, for example,” he says.

Recalling Nasser speaks to a time associated with pride and unity; recalling Sadat speaks in particular to military victory and the 1973 War, as well as tempering the revolutionary aspects of the Nasser era. Together they express the sentiment that Sisi will restore Egypt to greatness, that Sisi will be president not only of Egypt, but also of the Arab world.

Recalling Nasser speaks to a time associated with pride and unity; recalling Sadat speaks in particular to military victory and the 1973 War

The notion of Sisi as a unifying nationalist figure is an important one, given the straits in which Egypt finds itself. Nasrallah believes that “the Egyptian people will accept from him the difficult decisions required in the coming period because they will know that Sisi has the interests of the nation at heart. There will be hard decisions especially in terms of the economy and security.”

In his role compering the press conference, campaign spokesperson Tarek al-Nabawi, declares that “Egyptians will stand together as in the days of the High Dam.”

The nostalgia for the Nasserist period and its associations with unity and hope takes form with Sherif Hamdi’s rendition of Abdel Halim Hafez’s “Sura Sura” (Picture Picture) — introduced by Nabawi as a “great nationalist anthem.”

Hamdi then goes on to perform another song, itself called “Kammel Gameelak.”

It’s a catchy tune — perhaps even catchier that the pro-Sisi “Tislam al-Ayadi” that quickly became ubiquitous.

Before long, organizers, speakers and attendees are dancing and clapping, singing along in this ode to an Egypt that is strong and defiant, who smites her enemies, and a man who only puts Egypt first.

“You stood next to the revolution, oh leader, continue your favor, we all need you. You are our choice, the darling of millions.”