Houses out of Reach: The Expansion and the Crowding

When you meet Ghanem , it is hard to imagine that the 11-year-old could be the source of any tension or a part of any problem. The child from Homs lives with his grandmother, a cancer patient, after his father was arrested in front of him a year ago. The secretive Ghanem finally agreed to tell us his story after his two Jordanian friends convinced him to share it. He can hang out and play with them when they are together in the neighborhood, but at school it is different: Ghanem, who has lost two full school years, attends an evening-shift school in an all-Syrians class, while his Jordanian fellows go to the morning shift.

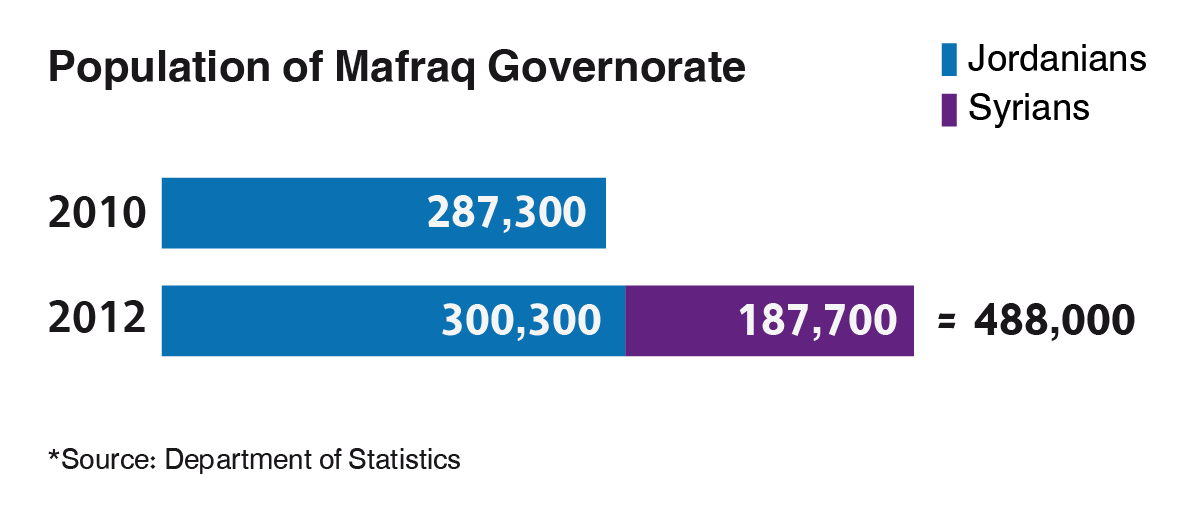

But Ghanem, who lives in a three-story apartment building fully rented by Syrian families, is actually in the middle of a crisis, a housing crisis. His family, like many Syrian families we’ve met, depends on donors and charitable organizations to pay their rent. The fact that donors and organizations are willing to pay higher rents, in addition to the first wave of Syrian refugees who legally crossed the border and spent most of their savings in a few months, caused the average apartment rent in the city to almost triple in the last three years. The demand for housing increased by 19 folds since the beginning of the Syrian crisis, as the need for annual housing units escalated from 660 to 12,000 units per year, according to a report by the Ministry of Planning and International Cooperation.

Zuhair Mostraihi, retired Jordanian army officer, is caught up in this crisis. Four years ago, he used to pay 120 JDs a month for the house he is renting, an amount that kept increasing over the past years. Today, he pays 250 JDs per month, and his customary annual lease was shortened by his landlord to six months.

“My pension is 300 JDs, and I have a son and a daughter in college, and two more in their last year of school sitting for the General Secondary School exams,” said Mostraihi, who runs a barber shop with his sons. “I have another source of income that helps me get by, but what about the fellow citizen who works from 6 am to 6 pm for 200 JDs? When can he work a second job, and how will he be able to afford a place to live?”

An example of such a citizen would be the son of a retired government employee, Bassam, who says that he has lost hope in getting married anytime soon, since the average cost of renting a small place to live exceeds his entire salary. “Over the past few months I have seen my neighbors’ rent go up from 100 JDs to 300 JDs. Moreover, landlords may also demand that payments be made in advance”.

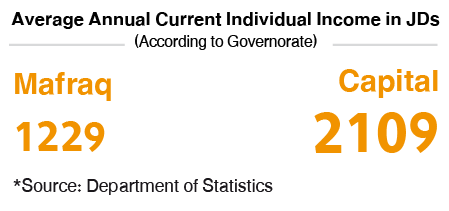

A way to understand this hike in prices is to compare these numbers to similar spaces in Amman, usually rented at similar rates despite the fact that the average monthly income in Mafraq is less than that in Amman by 880 JDs. In addition, the poverty rate in Mafraq is 19.2% compared to the national average at 14.4%, according to a 2010 income and expenditure survey.

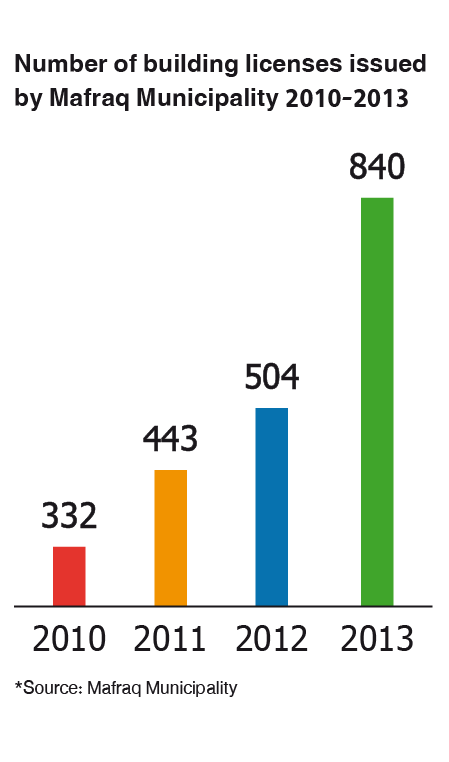

But not everyone gets the short end of the stick when it comes to this crisis, since for every person paying higher rent, there is a landlord and a property owner increasing his profit. Also, there are the real estate developers, who have been attracted by the potential of these high profits. According to the Ministry of Planning and International Cooperation, a construction boom in the city is expected to provide 3,700-5,600 new housing units.

Mustafa Abu Elaim, whose business ventures extend from cattle and car trading to real estate, confirmed that he’s benefited from the crisis, which –according to him – hurt most of Mafraq’s residents. Abu Elaim says that most Mafraq residents are employed “by the government or the army, and their salaries don’t allow them to pay 300 JDs a month in rent”. (According to the General Statistics Department more than 61% of the working force in the governorate are employed by the public sector). But he also admits that like many other owners of spaces to rent “he is looking for maximum revenue as a priority”, and while he has no preference between renting to a Jordanian or a Syrian he “will not pass on a monthly rent of 300 JDs for someone who is willing to pay 100 JDs only”. He adds, “even if I did, I will be solving one person’s problem. I will not solve the whole problem, or lower the market prices (by myself)”.

This wave of escalating rent rates affected Syrian refugees as much as Jordanians. Hamida Rahal was displaced with her sons and their families over two years ago from Homs to Damascus, and later fled to Jordan. But the donations and humanitarian assistance are no longer reaching her. “There were donors touring around the houses and checking on our needs, but we have not seen any of them in seven months”. Hamida, like many others, had to move her family to live in a space for lower rent after her landlord kept increasing their rent rate with the expiration of every three-month leasing contract. A charitable organization is paying the new rent.

One of these charitable organizations that help Syrian refugees secure their basic needs, with residence being on top of their lists, is “Rohama’ Bainahom” (Merciful Among Them). According to Mohammad Zyoodi, vice chairman of the organization, after working for more than a year as individuals, a group of volunteers came together and officially registered the organization, especially as the numbers of refugees kept mounting. Zyoodi said that the members of the organization tried to take advantage of their own business connections to reach to “donors from the Gulf region, especially Saudi Arabia”. He admits that he felt the displeasure of Mafraq’s local residents for being excluded from the organization’s charity work, but he considers helping Syrians to be the priority and the purpose of the organization.

“There are poor Jordanians and poor Syrians, and we try to help them, but a refugee family that arrives to Jordan with nothing other than the clothes they’re wearing is in a more dire need for every bit of assistance”.

The organization reaches 60% of the Syrian families in Mafraq according to Zyoodi, but “the wives and children of the martyrs” are especially looked after by the organization by leasing six furnished apartment buildings to provide them with proper residence.

“They have the right (to housing) more than others, and because women on their own could be pushed towards making mistakes (sin)”, in Zyoodi terms, who emphasized the fact that these building have “keepers/guards” carefully selected from the group of “devout older men” who deny access to anyone who is not carrying an entrance permit issued by Zyoodi’s organization. Male children over the age of 12 are not allowed to live in the building.

More work. Fewer Opportunities.

The assistance Hamida is receiving is barely helping her and her sons survive, especially that her sons “work for two days, and sit home for ten”. Like any non-Jordanian, they are not allowed to work without an official permit.

Permits have not been a real obstacle to many Syrians, as they managed to find jobs because they accept much lower wages than their Jordanian counterparts.

Abdallah Sa’aideh, former Mafraq governor, confirmed this, pointing to the cases of Syrian families working at the governorate’s farms during harvest season. Syrian workers work in groups of 15, a group usually being comprised of related family members, for 8 JDs per day per person compared to 20 JDs per day for Jordanians or Egyptians. This may not sound like a lot, but for a family of 10 working members this could be “a fortune for the family”, according to Sa’aideh.

Ismael Eleimat , an employer in the field of construction and interior design, sees Syrian workers in Mafraq as a source of real competition to Jordanians, primarily as a result of the lower compensation they ask for. “We cannot work at such rates. If I want to buy a cylinder of (cooking) gas I’d have to pay 10 JDs. A Syrian is willing to work all day for 4 JDs. If an owner of a building under construction decides to hire Syrian workers to do the finishing work, it will cost him one third of what it would cost to hire Jordanians.”

Despite this competition Eleimat said he only hires Jordanians because they need the jobs more as a result of the high cost of living. “Gasoline and utility bills and rent and taxes,” and other expenses that, according to Eleimat, “Syrians would not have to endure”.

The same reason that caused Eleimat to pass on hiring Syrians is the reason other business owners are jumping on the opportunity to hire them, but with some other reasons to factor in as well. Abu Anas , who owns a series of restaurants in Mafraq, said that he gives the priority in filling vacancies to Syrian and Egyptian nationals ahead of Jordanians, “not because the lower wages, but for reasons that have to do with work culture”.

Abu Anas added: “It’s very rare to find Jordanians willing to fill such positions,” referring to customer service and cleaning. “There are Syrians who asks for higher salaries than Jordanians, but the Syrian worker is experienced and is willing to actually work, while the Jordanian wants a desk and a chair”. The business owner does not hide his preference to hire Syrian workers “for their ability to attract customers with their hospitable and courteous attitude” compared to what he called the “rigidity” of the Jordanian worker, his inability to deal with customers’ moods and demands, and his tendency to “cause problems”. .

At the same time, he admits that some other reasons for favoring non-Jordanians stem from the Jordanian worker’s ability to ask for his legal rights. “The Syrian or Egyptian worker has no problem working for 12 hours for overtime pay, but the Jordanian will tell you that the law limits the working day to eight hours only. Also, the Syrian or Egyptian commits for a longer period and doesn’t have as many social obligations. A Jordanian takes too many days off and may quit if he gets a better job”.

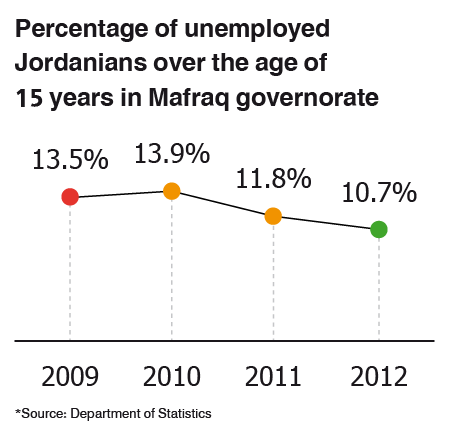

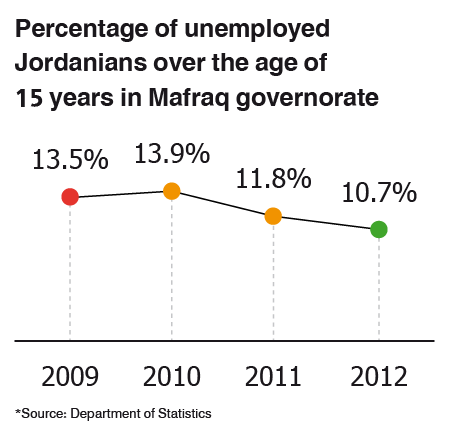

That said, there are signs that the presence of Syrians in Mafraq caused a significant rise in commercial and economic activities, creating new employment outlets along the way. According to the reports of the General Statistics Department, there has been a continuous decrease in unemployment rates in Mafraq between 2010 and 2012.

The story of Rakan Shammariat his current workplace is one example. He had lived all his life in Amman, but he recently moved to Mafarq to work as an accountant at a busy new fruits and vegetables shop owned by some of his family members. “Back in the day there was no activity after 6 pm. Today the shop is open 24 hours a day, and customers are constantly coming in and out, even during the night hours”.

Rakan identifies his customers as mainly Jordanians and Syrians. But a lot of people from the Gulf area and foreigners who work with organizations at the refugee camp frequent the place as well. In addition to the fruit shop, Rakan’s family has recently opened a sweets shop, in which they employed more Syrians than Jordanians, since “it’s their specialty”.

Bustling Trade

Syrian refugees in Mafraq have brought in more than price hikes and an additional workforce, as goods carrying the UNHCR logo became a familiar scene at the city’s markets. With the dependence of Syrian refugees on the United Nations Higher Commission for Refugees and other organizations to provide them with food supplies, they have taken to selling the excess of these supplies to secure the cash they require for other needs. These goods are resold to Jordanians at reduced prices, lower than the original shelf price.

There’s a market for UNHCR tents as well, smuggled from Zaatari, and sold at around 70 JDs per tent. They can be seen spread among Mafraq houses and on their rooftops.

Small businesses selling consumer goods also saw an increase in business as a result of the increase in population. Ali Lahham who runs a small bakery across Mafraq’s main street can barely find a minute to talk to us while picking up the hot, freshly-baked bread from a traditional stone oven, stacking it in front of the waiting queue. “Two years ago we used to go through 18 bags of flour every day. Now we need 28 bags a day, each weighing 50 kg.”

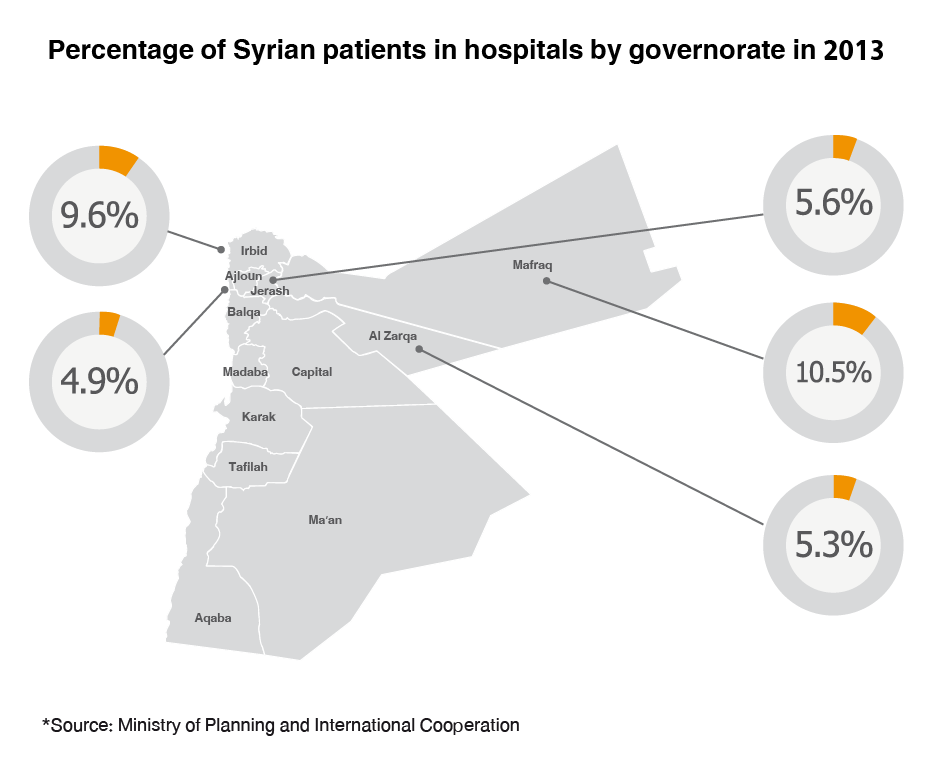

If bakeries are managing to cope with the increase in demand, other service providers are finding it much harder, especially hospitals. According to the Ministry of Health, the number of residents per available hospital bed in Mafraq was 1222 residents per bed in 2011, more than double the national average of 519. This bad situation became even worse with the flow of Syrian refugees, who now constitute 17% of the total patients at the Maternity and Children Hospital in Mafraq, and 12.6% at the Mafraq Public Hospital.

Hazem Khatib, a nurse at the public hospital, says that the management and staff are constantly concerned about the crowding of the hospital. “It is unbelievable that we have to tell the family of a patient suffering from a stroke or brain hemorrhage that we can’t admit him because we are out of beds!”

Basem Ranteesi experiences this mounting pressure on the city’s medical services every time he visits the hospital for his regular checkup or for his prescription refills. He says he has to wait in line for two to three hours, and that he is receiving “poor treatment” compared to a few years back when he rarely had to wait at all. He is not even getting enough of the medications he needs to treat his chronic nerves condition.

“I am a retired government employee and a chunk of my pension goes to health insurance, but I am only receiving half the quantity of medications I used to get. I have to buy the rest from outside (the hospital) because what I’m getting is not enough to last me the whole month. Some medications are not even available anymore.”

Just like hospitals, schools have also been subjected to overcrowding. According to former governor Sa’aideh, there are 12,000 Syrian students in Mafraq. Most of them are attending the evening shift at eight schools fully-dedicated to Syrians, and are staffed by retired and fresh-graduate teachers.

According to a report by the Ministry of Planning and International Cooperation, 35% of Mafraq’s schools are overcrowded. This required dedicating extra resources from the Ministry of Health to prevent the spread of viral diseases among students, especially since some Syrian refugees arrived from areas suffering from a humanitarian crisis. The Ministry of Health launched a vaccination campaign at the city’s schools against measles and polio, diseases that were reportedly eliminated from Jordan a few years ago.

Not Enough Water

Infrastructure networks that were not in the best shape before the Syrian crisis are also under pressure from the growing population. The water distribution network and sewage system are prime examples of that burden.

According to a report by the Ministry of Planning and International Cooperation, the number of official subscribers to the sewage system network in Mafraq is a mere 3342 (as of last summer). Mafraq mayor Hayel Amoosh, confirmed that less than half of the city’s residents had access to the sewage system in 2011. Meanwhile, the percentage of residents with access to the sewage system across the governorate stood at 15.2%, compared to the national average of 60%, according to the General Statistics Department.

Naturally, the water shortage that the city already suffered from was to get worse with the increase in its population. According to sources at Yarmouk Water Company, the volume of water pumped to Mafraq grew by 50 cubic meters per hour since 2010, to reach a total of 3650 cubic meters per hour. However, the city’s daily need is estimated around 3800.

As a result, Mafraq residents’ daily share of water dropped from 180 liters per person a day to 120.

Ismail Elaimat complained that water used now reaches his rooftop tank once a week instead of two, which forces him to resort to buying water from tank trucks. However, Yarmouk Water Company Sources deny that there has been a significant reduction in pumping frequency, saying that they only reduced pumping by a few hours, and that water is pumped to the city for one day a week, and for half a day to some villages.

As the water shortage is felt more and more in Mafraq, the business of selling water by tank trucks is booming.

On the road between Mafraq and Zaatari camp we met a worker attending to water wells that were once selling irrigation water to nearby farms, but now it is mainly selling water to the refugee camp. “The camp consumes much more water than what agriculture used to. We are selling about 1000-1200 cubic meters daily in the winter, and almost double that in the summer.

The governorate depends on water aquifers and groundwater, which also provides the northern governorates with their water needs, despite a rainfall rate that does not exceed 200mm annually. The high percentage of water lost in the decaying water network and the danger of sewage leakage into aquifers threatens Mafraq’s limited water sources with depletion and pollution.

According to Zaatari camp commander Zahir Abu Shehab, the camp consumes 4,000 cubic meters of water per day. The waste water and sewage from the camp is contained in cesspools and ground septic tanks, that could leak into the water aquifers below the camp, according to former governor Sa’aideh.

According to a development program designed by the Ministry of Planning and International Cooperation, the government is supposed to spend more than 2.56 million JDs in 2014 to expand the sanitation network, maintain the water networks, and dig more water wells in the governorate.

Waste Management Burden

The rapid growth in population and consumption is clearly (and visually) reflected in the amount of waste produced by Mafraq. A visitor to the city cannot help but notice the piles of trash accumulating on the sides of the streets and in empty lots – a problem, like many others, that preceded the arrival of Syrian refugees.

Mafraq Mayor Hayel Emoosh estimated the amount of waste produced by Mafraq at 200 tonnes a day in late 2013, compared to 80 tonnes a day in 2010. The municipality is no longer capable of managing this doubled amount of waste, especially with the limited number of trash-collecting trucks at its disposal and the trucks’ need for maintenance.

Moneer Zoghol, whose household includes 10 people, most of whom are relatives of his Syrian wife, said “the trash bin that was once used by one house is now being used by 10 houses. The garbage truck that used to pick up trash once a week is passing by once every two weeks”.

The waste generated by the city of Mafraq, Zaatari camp, and 10 other Mafraq municipalities amounts to around 350 tonnes per day, and is collected at the Hussainiat landfill located northwest of the city.

According to Emoosh, The Ministry of Municipal Affairs has recently approved 400,000 JDs for six months, funded by the World Bank, to hire a private garbage-collecting service and buy six trucks to manage the flood of garbage around the city.

Development Promises

According to the government’s three-year plan to develop the Mafraq Governorate, there will be 75.5 million JDs specifically allocated to cater to Mafraq’s developmental needs in 2014. The amount will be increased to 79.23 million dinars in 2015, and will reach 85.18 million dinars in 2016.

These allocated sums are supposed to target the following sectors: 16% for public works, 15% for the environment, 14% for health care, and 13% for local development, in addition to projects to improve transportation, public education, and the water distribution network and sewage system.

The three-year plan lists in detail the exact amounts to be spent to reach specific goals, such as improving the quality of life of the governorate’s poorest residents, improving the quality of public education, making up for the shortage in medical professionals and medical equipment, restituting lots for agricultural projects, and creating employment opportunities outside the public sector. The plan also specifies the programs and projects that the government will be directly involved in to achieve these goals and resolve the issues.

The three-year plan lists in detail the exact amounts to be spent to reach specific goals, such as improving the quality of life of the governorate’s poorest residents, improving the quality of public education, making up for the shortage in medical professionals and medical equipment, restituting lots for agricultural projects, and creating employment opportunities outside the public sector. The plan also specifies the programs and projects that the government will be directly involved in to achieve these goals and resolve the issues.