By Doa Ali, translated by Takwa Masadeh

My mother and brothers didn’t want me to go to school because there are a lot of boys around it. I wanted to stay though, I tried to convince them many times but they didn’t approve.

Ikhlas, Mafraq, 16.

Ikhlas is one of many Jordanian girls who drop out of school with their consent or because they are forced to. School is rarely substituted with any other activity which practically turns them into captives in the homes that should’ve been their platforms to the world.

Those are the “Homebounds” and as the name implies, their world after dropping out from school, whether it was their decision or their parents’, becomes limited to the things that may occur inside the house in which they are staying.

During last year, King Hussein Foundation’s Information and Research Center (in collaboration with “Save the Children International” and the American Department of Labor) held one of very few studies regarding the lifestyle of those girls, examining the reasons of their dropping out of school and its effect on their development and future opportunities.

Even though the results of the qualitative study cannot be generalized given that the sample was relatively small, the results clearly indicate that those girls form a social minority that doesn’t get enough protection.

The sample included 46 girls who dropped out of school from Mafraq, Ma’an, Abu Sayyah village of Marka and Hittin refugee camp in Zarqa, and 40 of their mothers. The center’s researchers (females) conducted thorough interviews with them or brought them together in focus groups.

The researchers had difficulties obtaining parents’ permission to interview the girls, according to Hadeel Alamayreh, chief researcher on the study. In various cases the permission was conditional on the parents being present during the interviews, which mainly took place inside their houses, given that the girls are not allowed to go out.

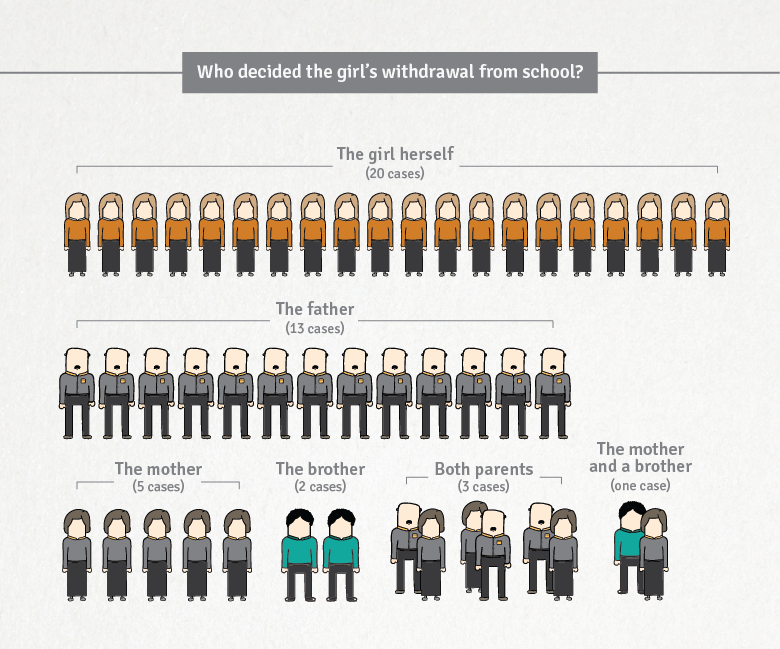

Who Makes The Decision?

According to the center’s director, Dr. Aida Essaid, research results did not match the researchers’ expectations. Child labor was the presumed frame of the study, as it was thought that girls were withdrawn from schools to handle household chores.

Study results showed that among the 46 girls, only two spend almost 7 hours a day doing chores. 44 girls said that they spend between 30 minutes to four hours doing chores, and the majority of them spend less than two hours.

This leads us to the question: Why then do these girls drop out of school? And who makes that decision?

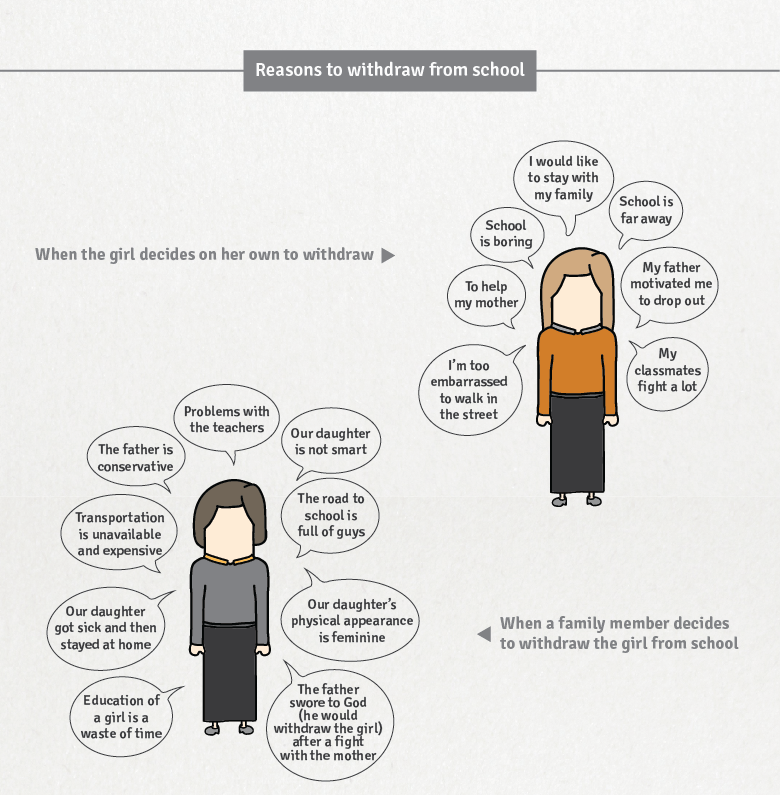

The study divides the reasons into two groups: girls’ reasons when they drop out and parents’ reasons when they decide to pull their daughters from school.

In the first case, the girls’ reasons appear to be a response to the economical or social status of their families, or to a direct wish from their families, although the decision is taken by the girls themselves. The girls’ wish to share the house chores with their mothers, and the parents’ encouragement to leave school topped the list of reasons.

There were other reasons, like feeling bored in school or the fact that school is too far from home. One girl said that she was deeply embarrassed to walk down the school’s street because it was “full of boys”.

On the other hand, the parents’ reasons –according to the interviewed mothers- were more direct and clear.

Difficulty in providing transportation was among the most frequently stated reasons. In all the areas included in the study, the primary and secondary schools were in different premises.

In most cases primary schools are close to residential areas and can be reached on foot. Secondary schools, however, are farther and they require a means of transportation, which most families interviewed considered costly. They also felt uncomfortable about having a male driver who is not a family member taking their daughter to school.

Her father withdrew her from school. It is in another village and needs transportation that costs 20 JDs. Because he is not working, he didn’t have the money. She cried and cried but he won’t send her.

Um Rasha, Marka, 48.

According to the study, various mothers said that their daughters “were not smart enough for school, and their academic performance was not high, this is why there was no reason to keep them in school”.

In some cases, the girl got sick and had to skip class for days or weeks and during that period her parents decided to just keep her home.

But the most despotic justification by parents for pulling girls out of schools was that their daughters’ “physical appearance was feminine”.

Some mothers said that the fathers decided to withdraw the daughter because “she started to grow and her body started changing”. The most conservative fathers also withdraw their daughters because they consider “girls walking down the street on their way to school is inappropriate” or simply because they wanted to pull her from school.

Home Confinement

With no school to fill up a good chunk of their time, what do homebound girls do with their days? And how does their withdrawal from school affect their future opportunities?

The direct impact of leaving school could be a feeling of being imprisoned at home. The study found that all girls interviewed have “limited to extremely limited liberty of movement outside home”. They are only allowed to go to a nearby shop, the market, houses of relatives, neighbors or married siblings, and this is only allowed in the company of the mother, father or an elder brother.

In most cases the girl “refrains from leaving the house on her own when she turns 12, which is when she reaches puberty and starts becoming an adult woman”, according to the study.

We don’t allow girls to go outside because they are like glass; if it breaks it can’t be fixed. Us older women can go anywhere, even to grocery shops that have men. But the younger girls are not allowed to go to shops with male shopkeepers, only to shops with female shopkeepers.

Om Maseera, Maan, 50.

Those girls’ opportunities of having a career or being financially independent diminish after their withdrawal from secondary education. But there are also psychological effects on their perception of their capabilities and potential, their understanding of the world, and their communication with it.

Homebound girls speak about their professional or academic ambitions using the past tense. They also describe simple wishes like going to the amusement park, or to going buy a dress as if they were wild dreams.

I was telling my mother yesterday how I wished I could go to Marka and see the lights and how people are living.

Maryam, Marka, 17.

The dominating relations that lead to the girls’ withdrawal are seen inside the house. Most of the girls said that they are closer to the mothers and the sisters than they are to the brothers. Elder male brothers were mostly described as “detached, busy with their own lives, or an authority of control”.

Younger brothers were described as “a source of disruption”, given that they always turn the house into a mess, which means that the girls will have to tidy and clean after them. As for the fathers, most girls said that they have no connection to them, they feel distant and their relationship does go any farther than “watching TV together”.

When I said to my father that I dream of standing on a theater he said “in your dreams”. There is no hope, there is nothing in our future.

Reema, Marka 15.

Legal Gap

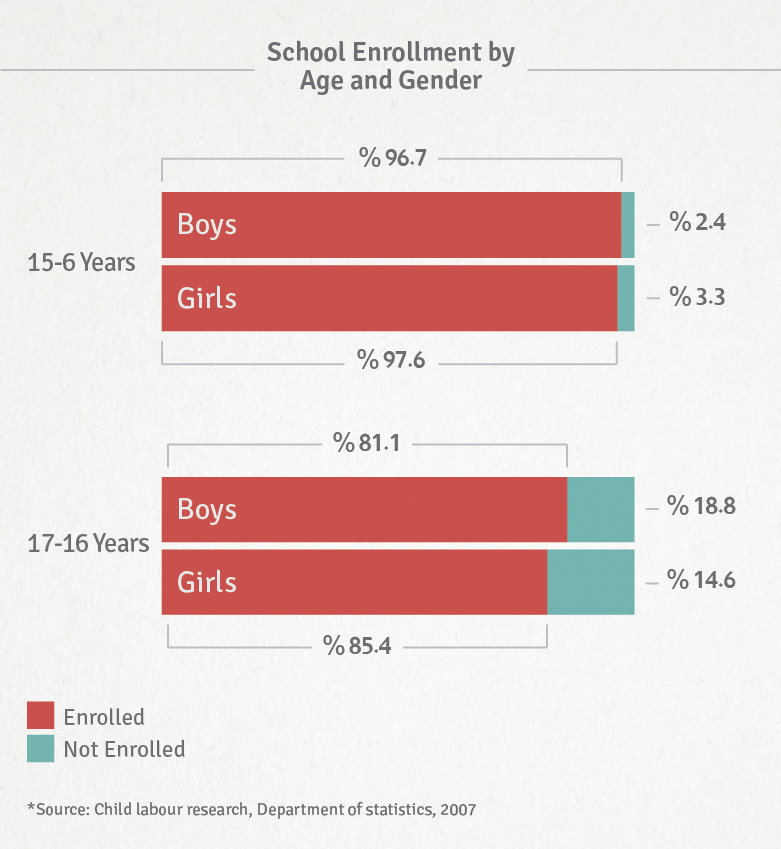

Legally, most of these girls fall into the legislative gap regarding their right to education. In Jordan, primary education until 10th grade is obligatory, and Jordan made progress in narrowing the gender gap in elementary education; almost 97% of children were enrolled in elementary education in schools in 2011. But secondary education is still not obligatory.

Although the percentage of male dropouts is higher than females’, the situation of females is particular because they don’t fall within the definition of child labor.

Although the percentage of male dropouts is higher than females’, the situation of females is particular because they don’t fall within the definition of child labor.

They either spend long periods of time without doing any work, or they do unpaid house chores that are excluded from the economic activity. This means that their work “does not necessarily qualify as economical exploitation, and as a result homebound girls are not protected by Jordanian legislations although they are highly prone to exploitation”, according to the study.

Jordan’s labor law prohibits hiring minors younger than 16 years of age and it assigns a specific number of daily working hours, but those restrictions only apply on “productive” labor that takes place outside the house.

Perhaps the situation of homebound girls is not as directly and instantly dangerous as the situation of working children outside their homes, but the effect of their isolation on their psychological composition, their growth opportunities and their self-fulfillment is just as bad on the long run.

An Arabic version of this article was published on 7iber last month.