After 3 years of absence, the Palestine youth orchestra (PYO) has finally returned to Amman, with a concert at the Franciscan School conducted by Vincent de Kort.

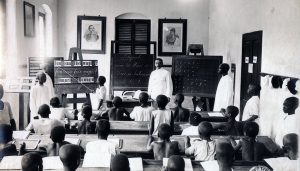

PYO’s last time in Amman was in 2014, over a sandy hill separating Huttin refugee camp from Marka north of the Jordanian capital. As Gaza was stepping into its second month of assault, the August sun boiled over the roof of an elementary school turned into a practice hall, filled up with a sublime crescendo, carrying us into the last movement of Beethoven’s fifth symphony.

Back then, we were a couple of Syrians joining the PYO for the 2014 season, and the symphony, with all its connotations of heroism and struggle and a finale evoking French revolutionary songs, seemed like a custom-made metaphor for everything we wanted to say, and certainly a worthier use of ink and paper than all the declarations and petitions condemning the occupation.

We were also excited by the fact that on the other side of lake Tiberias were young musicians who also had among them refugees, ex-detainees, and children of martyrs. With them we shared a passion for music, accompanied by all the usual challenges as well as additional ones, like spending double the time on checkpoints because of a music instrument, as we calmly explain to soldiers that music instruments don’t usually explode. We wondered how, all that time in Damascus, we allowed ourselves to think that we were alone.

There were differences too of course; they were good enough for repertoires that we wouldn’t dare approach anymore, not since 2011. They also said “Oboe” while we said “Hautbois”, each according to his previous colonizers who also decided that we will live in two separate countries instead of one, both of which we eventually lost.

And in today’s map, falling exponentially to fragments, the PYO remains one of the few concrete victories, and the only annual miracle where musicians of Palestine and the region are allowed to cross all kinds of normally uncrossable borders, and to spend two weeks in a collective resurrection of an impossible homeland.

The workshop usually closes with showcases getting more impressive by the year, and the PYO remains one of few Arab orchestras to maintain serious musical standards and a healthy work atmosphere. Having performed in venues like London’s Royal Festival Hall, Aix-en-Provence’s Grand Theatre, or Rome’s Academy of Santa Cecilia, the PYO maintained a special relationship with Amman, which had been, since the project’s foundation in 2004, the compulsory solution to the problem of gathering musicians from across Palestine with each other and with other Arab and foreign musicians.

As usual, the season brought with it names crossed out from the list at the last moment due to rejected permits, like Gaza’s musicians, whose absence hung heavy around the Orchestra, or other Arab musicians whose travel documents don’t usually evoke confidence in VISA offices. The similar logistical problems these Arab musicians face receive less attention, maybe because their invitation to perform is not a conscious statement about artificial borders or common destiny, as much as it is complementary and meant to fill the absence of Palestinian musicians.

The PYO preforms several roles, and the first one is demystifying Palestine, and not only for western audiences. Even for Arab youth, Palestine is an ambiguous entity, constantly shapeshifting between monotonous slogans and dream-like sceneries blurred away from maps and secluded in our inherited memory. Our participation as Syrians was an occasion to bring back Jerusalem, Haifa, and Nablus from abstract names and vocabularies of cheap schoolbook poetry into true cities made of streets, shops, and people we now know—people who are trying to create a different narrative of a country spreading beyond its borders. Some of them only knew the country occasionally, and others can hardly speak a complete sentence without the crutch of a second language, but all of them are equally Palestinian, which was new for those of us used to one-dimensional answers to what belonging to a place should mean, answers that most of us have a chronic failure of fulfilling.

With our second participation in 2015, some fantasies gave place to a more complex landscape, and we started learning how to read Palestine in a less poetic, more human way. And we understood that social groups during lunch breaks didn’t always form themselves randomly, that a series of social, religious, and political divisions was still present, even though it falls defenseless once there is music and the need for a unified voice.

The 2015 France tour was a big success, and the high level of performance considerably outpaced past years. The program choice, however, was less successful. Naji Hakim’s Baalbek, a tourist-brochure-like piece, was joyful, yet promoted a prefabricated image of the orient in dissonance with the one we’re trying to bring into awareness. We also barely managed to grasp the mannerisms of Berlioz’s King Lear overture, a work more suited for a professional orchestra wanting to delve deeply into French romanticism than for an annual youth orchestra that still hasn’t fulfilled the prerequisites for a proper interaction with Berlioz and his rhetorical complexities.

Since its founding, the PYO surrendered to the somewhat childish desire of constantly performing orchestral bestsellers, like Tchaikovsky’s piano concerto, or Beethoven’s Eroica. Despite being great works, these works are often chosen by default, and not necessarily in accordance with the orchestra’s capacities and quest for a personalized discourse measuring up to its uniqueness. On the other hand, the 2016 season brought signs of a refreshing change of pace, in the cautious approach to contemporary classical music with Graham Fitkin’s Metal, and some classic Arabic songs that were reinterpreted more imaginatively than usual.

The last Amman concert was probably the first in PYO’s history that was solely based on 20th century music, with Ravel’s Bolero, and excerpts from Prokofiev’s Romeo and Juliet. These attempts might encourage the orchestra in the future to challenge itself and its audience with more experimental and well-researched programs, instead of the common, automatic choices, or the couple of classic Rahbani songs that confine the Palestinian cause to the nostalgia of what it was 50 years ago.

It’s necessary to point out that the mere existence of a Palestinian orchestra is not, by itself, the purpose, and that its existence does not make any statement unless the PYO artistically proves itself. Because the PYO’s primary goal is to elevate Palestine from its absurd current reality—a tangle of green and red lines, departments and permits—and to give it the voice to tell a different story. Its members work very hard, keeping up with other youth orchestras around the world and refusing to play the heartstrings of victimhood. Yet, some marketing practices still strengthen these misconceptions, like the announcement of the last Amman concert, which didn’t even bother to mention the program or the names of the conductor and soloists—tiny details indicating that music still comes in second place, and that attending the PYO still risks being a blind duty to the cause, or worse, a display of social prestige.

The PYO aims to change all that, and to plant the roots of a durable orchestral practice in our region. But its true magic remains in its overwhelming energy, in a vision of classical and Arabic music that belongs to here and today, and not a result of any legacy imposed by history or geography. With these musicians, Palestine becomes a seasonal plant blossoming wherever they happen to gather, to rehearse both the upcoming concert and what true homeland should feel like.