Multimedia: Mo’awiya Bajis, Ahmad Masoud and Sufian Al Ahmad

Translated by: Maria Nelson

Flying from Amman to Khartoum on December 18, 2015, a group of planes transported at least 800 Sudanese refugees. Some of those on board had been deported in handcuffs, others without members of their family or their official documents. This was the execution of the Jordanian government’s decision to forcibly return hundreds of Sudanese refugees to their country, just after breaking up an open-ended sit-in they had held in front of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) headquarters in Amman. The demonstrators had called for improved living conditions and accelerated resettlement procedures.

Jordanian government spokesperson Mohammad al-Momani justified the swiftly implemented decision to remove the Sudanese refugees at the time, saying it came after UNHCR refused to give the deportees refugee status. However, UNHCR has stated that those forcibly returned had refugee status and documents, a group of which 7iber has reviewed.

The story began at dawn on December 16, 2015. It was the thirtieth day of the open-ended protest by Sudanese refugees. Early that morning, security forces came to the site of the sit-in and a rumor spread among the refugees present that Canada had opened its doors to them, that there was a large, warm shelter where they would be gathered, that they should board the buses that had arrived alongside the security. Those at the sit-in called others who were sleeping at home in the dawn hours and told them to hurry, to make sure not to miss the trip to Canada.

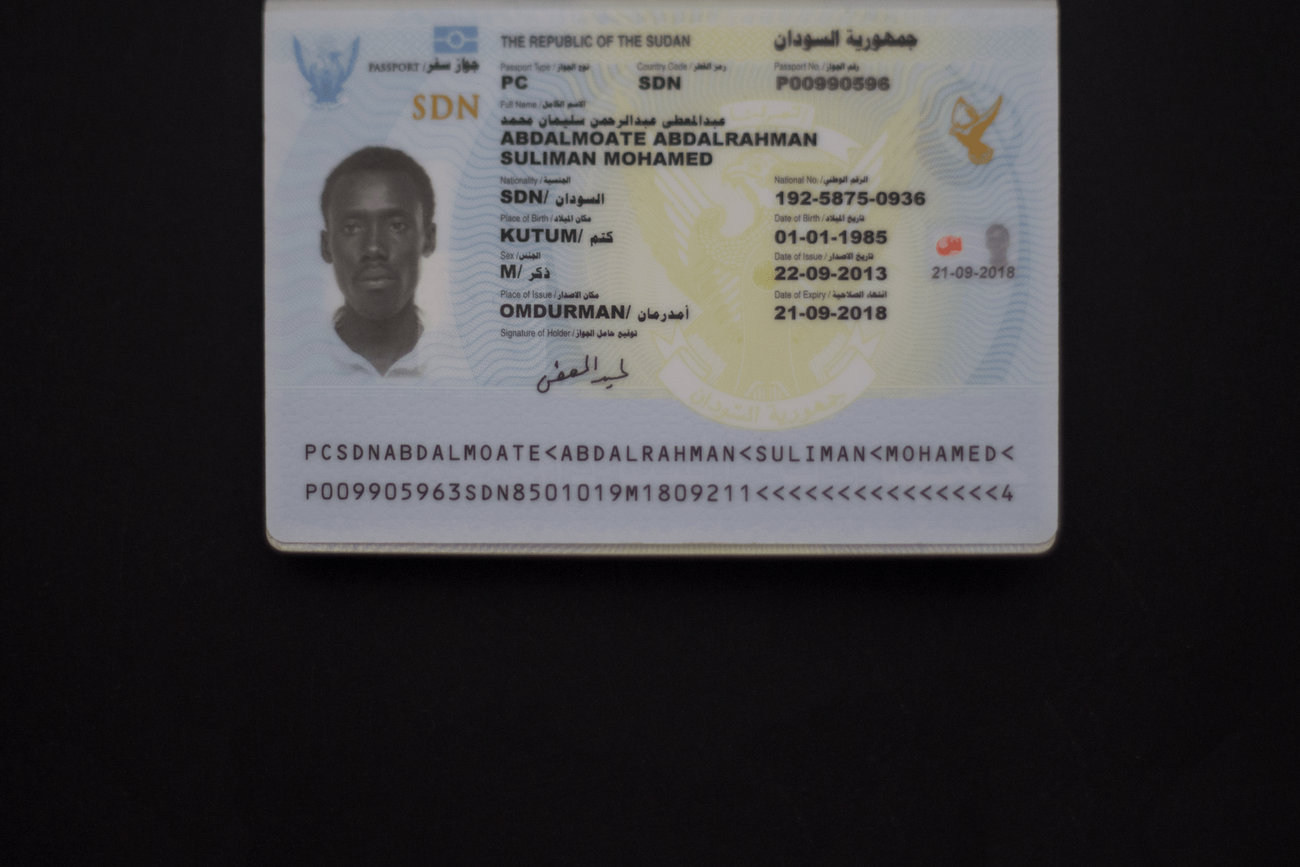

Nour a-Daim, Taj a-Din, and Ali were at the protest camp that morning. But Babakir and Hawa—a married couple—were sleeping at home, as were Abdel Mouti and Imam. They woke up to hurried phone calls from other Sudanese refugees, urging them to come quickly to the UNHCR headquarters. The callers told them the Jordanian authorities had promised a solution to their problems. But Ahmad and his wife Halima did not hear the news this way. They simply came to the UNHCR headquarters to renew their documents.

Everyone gathered at the UNHCR doorway. In front of them stood the security forces that had come to break up the sit-in, and the buses they believed would take them to the large shelter. But the dream of Canada began to turn into a nightmare when the security handcuffed the men.

“Why are they tying our hands if there is a solution?” Abdel Mouti asked his friend.

“Because there isn’t one,” answered the friend.

The buses headed for the airport, where the refugees stayed in an air shipping yard for two days. During that time, conflicting news spread about the government’s intention towards the refugees. Then, at dawn on December 18, Jordan began the mass deportation of the refugees. The action was taken on the basis of statements from the Sudanese embassy in Amman that the security situation in Darfur had improved, eliminating any danger to the refugees, according to media reports.

At the air shipping yard, the refugees understood that the Jordanian government meant to return them to Sudan. Trying to stop the deportation, they barricaded the door to the warehouse, which led to clashes with the security services that left many refugees injured by tear gas.

Throughout the events, Hawa was separated from her husband Babakir and infant daughter, Ayat. The mother was forcibly returned to Sudan alone, while her husband and child stayed behind in Jordan. The same scenario was repeated with Halima, who left a husband and two children behind.

Abdel Mouti returned to Sudan’s Darfur region after he was deported, but was struck by a car and killed three weeks later. His family says his death was at the hands of the Janjaweed militia.

Nour a-Daim, Taj a-Din, Imam and Ali tried to start a new life and seek refuge in Europe. Three of them made it there. Nour a-Daim drowned in the Mediterranean Sea.

A husband and a wife in different countries, and a child raised by another family

Hawa, a Sudanese woman living in Chad, asks me via cell phone about her nineteen-month-old daughter. She wants to know if her daughter, Ayat, is good at speaking and walking, and if she said anything during 7iber’s visit to the home of the family caring for her, in the village of a-Shouna a-Shmaliya, in the Jordan valley. Ayat lives there after her mother was deported to Sudan, while her father lives alone in Amman.

Ayat only said one word during 7iber’s visit, “Mama,” which she called the woman who has cared for her since she was an eight-month-old infant trying to get used to the weaning that was forced upon her by her mother’s absence.

Babakir and Hawa were married in Darfur, and chose to seek refuge elsewhere because of the war there, in which members of Babakir’s family were killed. The couple came to Jordan on a medical visa in 2014 and requested asylum. The same year, UNHCR recognized them as refugees. The couple received material assistance twice from UNHCR, but no regular support.

Like other Sudanese refugees, Babakir and Hawa could not find work easily in light of the current Jordanian labor law, which places heavy restrictions on refugees working.

In 2015, Ayat was born, and the family kept waiting for resettlement.

Babakir received a phone call at dawn on December 16, 2015. Another refugee told him about the rumor of immigration to Canada, and urged him to come quickly with his family so he wouldn’t miss his chance for resettlement. Babakir believed the rumor, and headed to the sit-in site in front of UNHCR headquarters, where he was surprised by what he calls “violent” security treatment. Security forces detained Babakir, tied his hands, and forced the family onto a bus.

Babakir, his wife, and child stayed on the bus for long hours before everyone got off at a large warehouse near the airport. There, Babakir witnessed the clashes between the Jordanian security services and Sudanese refugees who were refusing deportation. During the clashes, members of the security services heavily used tear gas inside the warehouse. Hawa was injured by inhaling the gas and was taken, alongside Babakir and Ayat, to Amman’s al-Bashir Hospital.

At the hospital, the doctor asked Babakir to take Hawa to the women’s unit, rather than the emergency room. So he took his daughter and climbed the hospital steps to meet his wife. But at the same time, Hawa saw a group of Sudanese people leaving through the hospital’s door, and thought that Babakir went that way. She left with the group by mistake, and was not able to return. That was the last time she saw her husband and daughter.

Security vehicles were parked at the door of the hospital to catch Sudanese refugees leaving the hospital and return them to the airport. In the chaos, Hawa did not know where Babakir and Ayat had gone. She was put in a car, taken to the airport, and from their deported on a plane to Khartoum, without her passport or any other documents. Nobody believed that her infant daughter had stayed behind in Amman.

Babakir searched for Hawa in al-Bashir Hospital and did not find her. He thought perhaps she had gone ahead of him and returned home by mistake. In the early dawn, he returned to their home in Jabal al-Joufa, although the key to the house had left with Hawa.

For hours, Babakir sat with Ayat in front of the house, despite the cold December weather. As the morning went on, he broke the door of the house and went in, waiting for any news of Hawa. She called him as she was boarding the airplane and told him what happened. There was nothing Babakir could do.

Before Babakir could absorb what had happened to his wife and family, he crashed into Ayat’s hunger, her need for her mother’s milk, and the reality of his caring for his daughter alone. He went to UNHCR for help caring for the child, or family reunification, to no avail.

The only help Babakir received was from an international organization that gave him milk one time, a month after he first petitioned them. But even this aid was no use, as the formula was not meant for Ayat’s age group.

Ayat was able to pass the obstacle of weaning, but Babakir was only able to care for her for three months. So a relative of his, Ibrahim, and his wife, who had both come to Jordan in the early nineties, volunteered to care for the child. They took her to their home in a-Shouna a-Shmaliya, where Ayat now lives with Ibrahim’s three children.

Hawwa’s Journey

In Khartoum, Hawa did not find anyone concerned with her situation after she left the airport. A stranger to the city, she did not know where to go. So she returned to the area she once fled, searching for her family.

“I returned to Darfur, and they told me that my mother and father were in a camp in Chad, so I came here. But they weren’t here, and I don’t have the money to search for them,” Hawa tells 7iber from inside one of the camps supported by international organizations in Chad. There, she lives with a family that she knows.

Hawa doesn’t have what she needs to search for her family in the other camps or obtain new identification documents. This makes her chances of being reunited with her daughter Ayat and her husband less likely.

With Ibrahim’s family in Jordan, Ayat has learned to walk. She has learned that “Mama” is Umm Muhammad. She uses “Baba” for both Ibrahim—who is raising her—and her father Babakir, who visits whenever he has enough money to do so.

Umm Muhammad says that Hawa is sometimes able to get in touch with the family. When she does, Umm Muhammad is eager to turn on the webcam, to allow Ayat to recognize her real mother. But that doesn’t happen, and the call ends with Hawa crying because Ayat does not respond to her.

Between Chad, where Hawa lives, a-Shouna a-Shmaliya, where Ayat lives, and Amman, where Babakir lives, the family continues to search for a solution, for a way to go back to the way things were, but in a third country.

Two daughters pay the price for the government’s deportation

Every day, Ahmad wakes up, helps his older daughter Aisha* get ready, and takes her to her school, located 10 minutes away from his residence in Jabal a-Nthif. He then hurries back home, afraid that his other daughter Fatima*, who he leaves alone sleeping in the house, may wake up.

Ahmad does not leave three-year-old Fatima at home alone by his choice. The other schoolchildren bother Aisha on her way to school, and he cannot leave her to be hurt, not after she has already survived a larger assault after her mother was deported alongside hundreds of others.

On the morning of December 16, 2015, Ahmad and his wife Halima*, the mother of his two children, went to the UNHCR headquarters in Amman to renew the identification card they received in 2014. Coincidentally, their renewal appointment fell on that day.

When Ahmad and Halima arrived, they were surprised at the presence of security forces and buses in front of the UNHCR, the rumor that a solution had been reached. The couple did not have much time to verify the details of the solution before Ahmad’s hands were tied and he boarded a bus with his wife and children.

“At six o’clock in the morning, I was with my family and the road was filled with police,” says Ahmad. “A policeman called me over and said: ‘Are you Sudanese?’ I told him I was, and he said: ‘Go over to your brothers.’ I told him that I had a renewal, and he said: ‘There is no renewal, you’re traveling.’ I responded, ‘If only, but through the UNHCR, not through the police.’ […] They handcuffed me and I got on the bus. My wife boarded the other one.”

Ahmad tells what happened that day, how they were moved from the UNHCR headquarters to a warehouse near the airport, where the deportees were placed to wait for the deportation procedures to be completed. He describes how refugees clashed with Jordanian security forces, who fired teargas at them, and how Halima inhaled the gas and was moved to Amman’s a-Toutanji Hospital.

During Halima’s stay in the a-Toutanji emergency department, Ahmad took his two daughters to their home in Sahab, to change their clothes and feed them after more than 16 hours of deportation procedures and clashes.

At that time, Halima finished her treatment, and was surprised by the general security vehicles waiting outside the hospital door to return the Sudanese people who had finished their treatment to the warehouse near the airport.

Halima says she was tricked twice: first, in front of the UNHCR, when she was told they were going to Canada, and then again when she refused to get on the bus waiting for her outside a-Toutanji hospital. She asked about her family, and security personnel told her they were all waiting for her at the airport, that Halima had to get on the bus so she could meet up with them.

Halima understood the truth when she arrived at the airport and was able to call her husband and confirm that he was at home. She asked the security forces to return her to her family, but they said she was lying.

“I even showed them my milk, to show them I was nursing,” says Halima. “Nobody believed me.”

Ahmad says that one of the security officers called him and offered for him and his two children to join Halima at the airport in 20 minutes. “I told him I couldn’t make it in 20 minutes, and to give me more time,” says Ahmad. “He refused, and told me ‘then we’ll send her off.’”

Halima was forced to board the plane to Khartoum, and Ahmad remained in Amman with Aisha, who was seven years old, and Fatima, who was one year and four months old.

Halima had not weaned Fatima before she was deported. For several days, Fatima refused to drink the formula that her father bought, until she grew weak and was taken to the hospital. After that, she drank the formula, becoming the first to get used to the new chapter of the family’s life.

Many times, Ahmad asked UNHCR to find a solution to reunite the family, or provide financial support to allow him to support two children alone, without his wife and with work difficult to find. He did not receive any help. So he had to live with other refugees to split the rent, not knowing the outcome of this decision.

After a number of months in that house, Aisha was sexually assaulted by Ahmad’s roommates. Ahmad informed UNHCR, and the accused were caught and referred to the court. The case is ongoing. Aisha and Fatima were taken to a care home, because it was not safe for them to be with their father.

The children stayed in a care home for around seven months, during which time 7iber met Ahmad. He would speak about his bewilderment, knowing that his daughters were being treated in the care home. He longed to be a father living with his family, even though he would visit the girls—once every two weeks at most. Aisha was improving psychologically and Fatima had lost the Sudanese dialect.

“She speaks Jordanian, not a word of Sudanese,” Ahmad says, laughing.

He tried to get his girls back, but the care home set conditions that he secure safe housing for them, and that their mother be present in the home. After efforts to return Halima failed, the care home returned Aisha and Fatima to their father once he rented a suitable home for them.

At the beginning of the girls’ stay at the care home, Ahmad was not allowed to open a line of communication between them and their mother. She was undergoing another experience, moving from country to country in an attempt to meet her daughters in a third country.

Halima’s Journey

Halima was able to get new identification documents after reaching Khartoum, and stayed there for approximately one month with a family she knows. After that, she travelled by car to the Egyptian border, crossed it, and requested asylum once more until she received recognition from the UNHCR in Cairo as a refugee for the second time, without financial support.

Five months after Halima was deported, Ahmad received approval for monthly family support in the sum of 160 dinars. Of those, he pays 100 for rent and bills, and sends 40 to his wife in Egypt. Halima uses the money for rent in shared housing with other refugee women. Before Fatima went to the care home, Ahmad paid 30 dinars for baby formula.

Halima and Ahmad were married in 2007, after a love story that brought them together through their university studies in Sudan. But Ahmad’s origins in Darfur left him subject to repeated detention in university, so he decided to go to Israel.

Ahmad walked through the desert in 2010 until he reached Israel and slipped inside in search of work. But the authorities caught him and sent him back to Sudan, where he was imprisoned for 13 days following his arrival at the Khartoum airport, because he was returning from Israel. Once released, he could not live with his wife because the Sudanese authorities put him under house arrest for five months in a house in Khartoum. All Ahmad could do was collect money to get identification documents with false names to travel to Jordan with his wife.

Ahmad, Halima and their daughter Aisha entered Jordan on a medical treatment visa in November 2013, and were recognized as refugees in December 2014, without material support. Ahmad worked in blacksmithing and painting after finding a house in Sahab. The family waited for resettlement in a third country, and little Fatima was born in 2014.

Now that Ahmad’s daughters have returned to live with him, he is having trouble answering their questions about their mother, especially Aisha’s questions.

“She asks a lot, ‘Why does everyone have their mothers with them, and we are separated from ours,’” says Ahmad. “This question saddens me so much. Then she starts crying, and her little sister cries with her.”

Four leave Amman, three reach Paris

Ali, Imam, Taj a-Din and Nour a-Daim: Four leave Amman, three reach Paris

In Trocadero square overlooking the Eiffel Tower in Paris, I stood with Ali, Imam* and Taj a-Din. They introduced us to the streets and districts they had memorized to get used to their new home. The three met each other in France by chance, and then discovered they had been together in Amman. They went through the same experience, forcibly returned to Khartoum from Amman, then traveling the sea to Italy, and then traveling to France.

They met by chance in Paris, with only one mutual acquaintance from Amman: Nour a-Daim, who drowned in the Mediterranean Sea.

The three young men didn’t hide their nostalgia for Amman. Imam says the streets of the Jordanian capital are cleaner than Paris, and that there are many memories he longs for there. Ali’s nostalgia is for the Jordanian dialect, to the extent of searching for show times of the Jordanian film “Theeb” in French cinemas.

“I am intensely connected to Jordan,” Ali tells 7iber. “It is part of the story of my life. You could say the beginning of my exile was Jordan, and I lived my most beautiful days there, even though they did not end well.”

Even thinking of their future life and longing for beautiful past memories, none of them has forgotten the details of the journey to France, which began after Jordan committed a “crime against humanity” by deporting them, according to Taj a-Din.

The three young men describe what happened after they arrived at the Khartoum airport, where well-known figures and regime representatives were present to receive the forcibly returned Sudanese refugees.

“They told us, ‘thank God you arrived safely in your voluntary return,’” says Taj a-Din. “They wanted to show the public that we arrived of our own will. The media cameras were broadcasting live,” he added, explaining the media coverage with the desire to portray Sudan as stable and secure.

After the refugees completed the security measures at the airport—questioning, pictures, and fingerprints—they were given 50 Sudanese pounds and left for buses, all in front of the camera lenses. The buses set off for one of the markets in Khartoum, but, once the refugees were far from the airport, security forces stopped the buses and arrested those they wanted to investigate. Some were able to flee, others were arrested, and a third portion who the authorities did not want to arrest remained on the buses, according to Taj a-Din.

Ali was one of those detained. He was held for three days, interrogated and questioned by the official authorities, he says, before a member of the security helped him escape. Taj a-Din says he was tortured and held for days, immediately after leaving the airport.

Imam was able to flee the arrests and reach his uncle’s house in Khartoum. His uncle was afraid of him staying at his home, and helped him travel to Libya two days after his arrival.

“There was no way for me to live in Khartoum,” says Imam. “With the ongoing arrests, I was afraid for my life all the time.” And so he began a new journey to seek refuge and “safety” in Europe.

Imam reached the Sudanese-Egyptian border with his uncle’s help, and then walked on foot for three hours to cross into Egypt. Once there, he got in a car that took him to the Libyan border. He crossed on foot for five more hours, and then arranged a car to Tripoli, where he stayed for six months. There, he worked in the tomato fields to raise the money needed for the smugglers to take him to Europe on the illegal rafts.

Imam’s Journey

Once Imam had the money, he entered “storage” in May 2016. Storage refers to a space where people who have reached an agreement with the smugglers live until their turn comes to travel. There, Imam described difficult living conditions.

After 26 days, Imam and a number of other young men came out of storage so they could inflate the rubber raft that would bring them across the sea to Italian waters. “Either you blow up the raft, or you get a couple bullets,” says Imam, describing the smugglers’ threat. “That day, they came in and said: you, you, and you, because you’re tall.”

“They told us: ‘Take the raft, bring it halfway into the water and blow it up […],’ says Imam. “ You couldn’t say no. Tell the mafia no? […] Fire behind and water ahead, what do you do? You’re dead one way or another. And anyways, if I wasn’t wronged in the first place I wouldn’t have gotten on the raft.”

The raft set off, with 350 people standing aboard, since the area of the vessel did not allow for anyone to sit. After eight hours, they arrived at the Italian island of Sicily, after losing a six-day-old Eritrean child whose mother had given birth to him in storage. He could not bear the journey. A young man from Mali, who was injured in his foot, also died, says Imam. “The smugglers shot him in his leg, and he bled out and died.” They threw the bodies into the sea.

Imam reached a camp in Italy, where his arrival was documented, his picture and fingerprints taken. But he was determined to continue his journey to France, and carried on by train until reaching Paris, where he requested asylum.

Taj’s Journey

Taj a-Din made it through the events at the Khartoum airport and detention, and then stayed with a family he knew in Khartoum. He was detained yet again after completing an interview with a satellite channel, speaking about the forced return of refugees to Sudan. He spent 45 days in detention and was tortured, he says.

Afterwards, the authorities asked him to participate in a televised meeting and state that the refugees returned to Sudan voluntarily. Taj a-Din agreed, and was able to run away from the television building on the day of the interview. He headed to Darfur, then to the Libyan border, where smugglers brought him to Benghazi.

In Benghazi, Taj a-Din worked at a chicken farm to collect the money needed to move to Tripoli. In Tripoli, he joined seven other young men who had made a deal with the smugglers, or “human traffickers,” as Taj a-Din calls them. All of them went to “storage.”

In June 2016, a small, stuffed raft set off from Tripoli to cross the Mediterranean Sea. Taj a-Din was on board, alongside hundreds of undocumented immigrants. Italian rescue teams found them seven hours later and transported them to a camp in Italy.

Like Imam, Taj a-Din wanted to reach France and request asylum there. He went, moving on foot sometimes, and hidden under train seats at other times, until reaching Paris in July. He turned to the French organization “Land of Refuge,” met with a Sudanese lawyer and began to seek asylum and citizenship. He obtained refugee status, and with it health insurance, housing, and a steady income that allows him to study French.

Taj met Imam and Ali in Paris, and each told the details of his deportation and the stories of those who were with him, including Nour a-Daim, who drowned in the sea. Ali knew the details of his story.

Ali and Nour a-Daim lived together in Egypt after fleeing to Cairo following the forcible return from Amman to Khartoum.

Ali lived with Nour in an apartment in Cairo’s Ain Shams area, and recorded his amnesty request with the UNHCR in Egypt, which was a glimmer of hope. But the UNHCR did not behave differently than in Jordan, which drove Ali to think of an alternative.

“The situation was moving backwards, the only alternative was the sea, and people were ready to go,” he says.

Ali was able to collect the money needed to travel to Europe, and Nour was not. The two agreed that Ali would go first, and Nour would catch up later, once he had the necessary funds.

Ali’s Journey

Ali reached Italy, then France, in a journey no less harrowing than those of Imam and Taj a-Din. The boat Ali was in alongside 200 others got lost in the sea, he says. “We felt we had gone the wrong way, and were not able to find rescue,” says Ali. “We ate dry bread, taamiya (falafel) and sardines […] a cup of water in the morning, and one more in the evening.”

For nine days, they remained like that, before a rescue team found them and brought them to Italy, according to Ali. He then traveled to France, where he received asylum and citizenship.

Nour’s Journey

Ali stayed in touch with Nour a-Daim after reaching France. “We heard that he went on the sea,” says Ali. “After a week, maybe eight days, we knew that he had been in storage for a while. Then we heard that the raft sank, and he was among the missing.”

Ali tells what he heard from survivors on the raft, that Nour a-Daim was among a group of people riding in a small room, called the refrigerator, and when the boat sank the door closed and they could not open it again. This made rescue difficult, and he died in the sea.

Today, the three young men are learning French in order to live a normal life. Ali and Taj a-Din became French citizens after receiving resettlement. Both now volunteer, collecting aid for new refugees and guiding them through the procedures of the required interviews. Imam is still waiting for his citizenship to be accepted. He believes this will be a way to reach his mother, who he has heard nothing of since 2003. He dreams of bringing her to live with him, studying accounting and beginning a professional life.

Those aspirations do not make the refugees forget the violations they were subjected to, in which the Jordanian government, UNHCR and the international community participated, according to them.

“Everything that happened in Jordan was illegal and immoral,” says Ali. “We call on the Jordanian to apologize to us, to our families, to the victims of war and the displaced at the national level […] we are greatly disappointed in UNHCR and the Jordanian government […] the international community has no morals.”

When deportation means death

After the deportation, the Sudanese embassy in Amman said, responding to questions from Jordan’s Center for Human Rights: “These Sudanese people do not warrant asylum because they are ordinary people. They have no political reasons, they are not in the opposition, and the overall security situation in Darfur is more stable than it was before.”

A year and a half ago, a few days after the Jordanian government’s decision to deport the Sudanese refugees was carried out, 7iber visited the house of Salim*, a Sudanese refugee still in Jordan. He had been living with a group of Sudanese people in Amman. He spoke with 7iber about his friends and roommates who had been deported, and particularly Abdel Mouti, his childhood friend whose passport he was still holding onto.

Days after that visit, Salim learned that Abdel Mouti had been killed in Darfur. And months after that, he learned his other friend, Nour a-Daim, drowned in the Mediterranean while trying to get to Europe. And the news of death or detention continued.

Salim told 7iber the stories of his friends once more, but this time under a false name. He is afraid to express his opinion after the “deportation penalty” his friends paid for their sit-in, he says.

Salim and Abdel Mouti were friends since elementary school. They studied together, graduated together and, after completing their studies, fled the conflict in their area to one of the camps in Darfur together.

Years later, the two friends travelled from Darfur to Khartoum together. They had decided to seek refuge in Jordan after witnessing the Janjaweed militia enter the camp they lived in, killing many and raping the women, according to Salim, without the intervention of international organizations that were present.

Salim and Abdel Mouti came to Jordan on a medical treatment visa, requested asylum, and received it. But that did not provide them with an income from UNHCR, so they lived with other young men and searched for day-to-day work to pay rent and expenses. That is, if they could work without being caught by the Ministry of Labor inspection teams.

Abdel Mouti’s Journey

The day of the deportation, Abdel Mouti received a call from a friend in front of the UNHCR building, telling him there were Jordanian officials promising a solution to their problem, and that they wanted to move them to a big place, in order to find a solution so they could travel to Canada.

Abdel Mouti woke everyone up and told them the good news. Salim was feeling sleepy and did not respond, so Abdel Mouti went himself. Salim went back to sleep, and that was the last time the two met.

In front of the UNHCR headquarters, Abdel Mouti was handcuffed and forced onto a bus, which made him doubt that any solution was coming. After arriving at the air shipping area, he knew he was on the way to a forcible return to the country he fled, according to what he told Salim via cell phone.

Abdel Mouti asked Salim to send his clothing and passport to Sudan for him, but the cost of mailing them was more than Salim could pay.

“I called him and said that sending the bag cost 105 dinars, and I couldn’t pay,” says Salim. “He told me, ‘okay, I will go to Darfur and find a solution,’” adds Salim in a wavering voice. He says this was his last phone call with Abdel Mouti.

Three weeks after that call, Salim received news of Abdel Mouti’s death. He had been struck by Janjaweed vehicles in an event that Salim says was part of a series of ongoing car attacks by the Janjaweed in Darfur.

Salim has kept pictures of Abdel Mouti and a video clip of Nour a-Daim during the sit-in at the door of the UNHCR in Amman. In it, Nour starts laughing, telling jokes about the heavy rain falling on them during the sit-in, before he drowned in the Mediterranean.

Jordan, Sudan, and the UNHCR: Collective disavowal of responsibility

The official Jordanian justification for deporting the Sudanese refugees relied on a lack of recognition as refugees. But Article 21 of the Jordanian Constitution bans the return of political refugees to their countries. Article 3 of the 1984 Convention against Torture, which Jordan signed, prohibits in principle the return of any person who could be in danger of torture to their country, according to Ayman Halsa, lawyer and professor of international law at Al-Isra University.

Halsa says that, beyond agreements and international laws, the Jordanian government had to “respect” the Residency and Foreigner Affairs Law, which stipulates deportation procedures, starting from notifying the individual and giving them the right to challenge the deportation decision.

The ARDD-Legal Aid organization, which is responsible for the legal protection of refugees under a memorandum of understanding between it and the UNHCR, says that it received notification from the government about the deportation, but not any formal confirmation of the decision. This is what violates the Residency and Foreigner Affairs Law, which stipulates that a confirmation document must be submitted to the person whose deportation has been decided, or their representative, and that the individual may dispute the decision before the Administrative Court.

Samar Muhareb, ARDD’s executive director, says she does not know what legal basis the Jordanian government relied upon when deporting the refugees. Muhareb did not comment on whether the government violated any conventions or international treaties.

Although Muhareb says that refugees should not be deported in practice, she does not hold the Jordanian government responsible for the deportation of the Sudanese refugees. “The UNHCR is also responsible,” she says. “All the countries that are not finding a solution to the refugee crisis, what can Jordan do?”

On the other hand, the Jordanian government coordinated—through the Jordanian Ministry of Interior—with the Sudanese Ministry of Interior about the deportation, according to Jordanian newspaper Al-Ghad. The Sudanese embassy also announced meetings it held with Jordanian authorities, in which the embassy opined “that the UNHCR does not have the right to grant them refugee status,” which Halsa considers to be another violation of the refugee protection system.

“Coordination with the Sudanese government, this alone is a crime,” says Halsa. Refugees or asylum seekers must be treated in a confidential manner so they are not later subjected to torture, he says, and the government should not be the basis for information on the human rights situation without paying attention to international reports, especially since it is a party to the problem.

In the Sudanese embassy’s response to the National Center for Human Rights’ questions, said that there was suspicion of human trafficking in the entry of the Sudanese to Jordan. According to the embassy, they came under promises of travel to Europe and money, “and therefore, they do not deserve asylum,” especially since “the security situation in Darfur is more stable.”

The embassy appreciated Jordan’s efforts to break up the sit-in, clarifying that Jordan had not requested “any assurances from the embassy that the returnees not be subjected to any violations of their rights,” but that “the Sudanese authorities do not have any political position [and are not] in the process of taking action against the returnees.”

The refugees we interviewed placed the greatest measure of responsibility with UNHCR, accusing the agency of failing to take necessary action and intentionally not responding to calls for aid and visits following the deportation. The official spokesperson for UNHCR did not comment to 7iber about the situation of the refugees following their deportation or about the efforts being taken to reunite divided families.

The National Center for Human Rights called on the Interior Minister at the time, Salama Hammad, to respond to questions about the refugees who were forcibly returned to Sudan, but did not publish any response.

Halsa places responsibility for what occurred with the government, UNHCR and the international community. He calls for UNHCR’s work to be monitored, and denounces the discrimination practiced by countries receiving refugees, which makes resettlement more difficult for some.

Muhareb says the Jordanian government informed ARDD of developments as they happened, indicating that the government did not have the ability to meet the demands of the Sudanese refugees, in her opinion. She said that the continued protest and some media leaks had contributed to the deportation decision being sped up.

ARDD is currently working to help those remaining in Jordan, to improve their mobility “because the deportation scared those who remained,” Muhareb says, pointing out their constant calls on the government to leave them alone.

The night of the deportation, Salim was overcome by sleepiness. So his friends left him and went to the UNHCR headquarters to find out what solution had been said to be promised by the Jordanian authorities. They went, and not one of them returned. And Salim learned a useful lesson: that a demonstration in Jordan could send him towards death once again.

Salim says that he expected that the authorities would not put up with the sit-in, that they would break it up violently and detain some demonstrators. “But deportation? That wasn’t expected at all.”

Since that time, Salim, a 30-year-old, has moved to another house, with cheaper rent. He has become a leader of the council of Sudanese people in Jordan. He helps collect aid and communicates with a large number of refugees. But he still has not received any monetary support from UNHCR, even though he was recognized as a refugee two years ago. Sometimes, he works odd jobs, such as building. He has to run from the Ministry of Labor’s inspection teams every now and then.

Salim is trying to build a life in Jordan until he receives resettlement. That could be a long way away, especially since he has not yet been called in for an interview. But he dreams that one day he will begin a new life. He hopes to study water and agricultural engineering. Sudan, he says, is “vast land and abundant water,” and his studies would allow him to work for himself and for his country.

Read More:

Africans in Jordan: Second-tier refugees

Sudanese refugees sit-in demanding resettlement (AR)

Jordan forcibly deports 800 Sudanese refugees to their country (AR)

Sudanese refugees tell how the escaped deportation (AR)