Zahra Olando was in her mid-twenties when she left Pakistan to settle in Jordan in 1967. She brought along her husband and two children, who were two and seven years old at the time. They joined other Pakistani families that had preceded them here, all of whom worked in farming tobacco and vegetables.

Zahra’s family, which was among the first groups of Pakistani workers to migrate to Jordan, came here from the province of Sindh. Originally, however, Zahra hails from the province of Balochistan, a nearby region.

Zahra says that when the family arrived to the area, they were originally headed towards Saudi Arabia to perform the Hajj. During a journey overland that lasted a few months, the family crossed Iran, Turkey, and Syria.

Since they left their country without sufficient funds for the trip, they lingered at each stop along the way for a month or more, and worked to gather funding to finance their journey until the next stop.

When they arrived in Jordan, they knew it was the place that they wanted to settle down in. As Zahra says, Jordan was a country that enjoyed security and also offered much higher earnings for farm work compared to Pakistan. They had also been farmers there, mostly of rice, wheat, sugar cane, and corn.

Zahra, whose husband passed away 10 years ago, speaks in Sindhi, and some expressions in broken Arabic. During her interview, her grandson Mohannad (16 years old), who speaks Jordanian dialect fluently, took care of translation.

Zahra says that during that period, Pakistani workers primarily worked in tobacco farming. The families spent half the year working in tobacco fields in Irbid, Madaba, Al-Mawbis and Ma’in, and the other half in the valleys, where they worked farming vegetables.

She says that, at the time, tobacco farming was flourishing, and that it was ideal for Pakistani families that brought along their children, not only because their earnings were higher than those from vegetable farming, but because the children could work the field as well.

She remembers that men shouldered harvesting tobacco leaves while women and children handled sewing the leaves into chains with needle and thread.

The flourishing of tobacco farming during the period of the Pakistanis’ arrival was due to governmental support of this type of farming as well as the possibility of selling the crops to tobacco companies working in Jordan.

But the situation changed in the beginning of 2000, when money exchanges stalled. Consequently, a 2004 law was passed, which nullified a tobacco farming law passed in 1952 in order to administer the tobacco industry.

The government relinquished its control over tobacco farming. It was an expensive and soil-exhausting industry, and this decision made its management a personal choice for the farmers. The decision nearly killed the industry.

Afterwards, Zahra says, life in Jordan was no longer as easy as it was before. The prices of the vegetables that Pakistani families had been dedicated to farming in the valleys and regions of Al-Shafa declined year after year.

This occured at a time when the expenses of farming and the cost of living were increasing. As they escalated greatly, so did fees for work permits and visas, as well as fines imposed for lateness in requesting them.

In addition to the two children she brought with her, Zahra gave birth in Jordan to three more sons and one daughter. Her family, like other Pakistani families, still follows the same pattern of work: they labor in farms and move with the seasons between the valley and Al-Shafa.

The difference is that the families that came to Jordan are comprised of two generations that grew up here, adding two other generations of children: their children, and their grandchildren.

Zahra Olando with her family in Dir Ala. Photo by Mohammed Zakaria.

Zahra has not visited Pakistan since her arrival fifty years ago, and neither have her extended family members, with exception of her son Shafiq (54 years old).

The overwhelming majority of Pakistanis in Jordan, according to Zahra, have never set foot in their motherland. This is because they barely manage to support their large families, and cannot afford the cost of a visit.

She now lives with her five sons, their wives, children, and grandchildren, in a camp of ‘arishas. These are box-like structures constructed from wood and iron frames and clothed in thick plastic. The family’s camp is located beside the farm where they work in Dir Ala.

This camp is one of hundreds of similar camps belonging to extended Pakistani families, distributed throughout Dir Ala, Al-Karameh, southern Al-Shouna, and Al-Safi valley. The Pakistanis say that this form of residence is appropriate for the nature of their work, which requires moving during the year between the valley and Al-Shafa.

In addition to moving between farms, they reside on them to guard them. Thus, the vast majority of these families live in ‘arishas, due to the ease of packing them up and moving them from place to place.

The family stays at the camp during winter, and when the time comes to travel at the start of the summer, one of Shafiq’s brothers remains at the farm to guard it while the rest of the family moves to Al-Labban, where a cucumber, tomato, and zucchini farm is located. The farm is owned by their Jordanian guarantor, who issues them work permits.

The family offers labor, and the guarantor offers land. In the end, the two sides distribute the expenses and the profits among themselves.

Arishas where a group of Pakistanis live, and the farm where some of them work. Photos by Mohammed Zakaria.

Shafiq, who came to Jordan when he was two years old, visited Pakistan three years ago for the first time in his life.

He says that what prevents Pakistanis from returning is that most of them have not invested in Pakistan. They have spent and continue to spend all of what they earn to support their families, pay visa fees, work permits, and fines.

This is because Pakistanis who live in Jordan for 50 years do not enjoy a special status, whether in regards to work or residency. The laws applied to them are the same ones applied to any recently arrived migrant worker.

Shafiq adds that returning to Pakistan, without owning land or a house, means having to work in the employ of others. And in the context of worsening salaries for agriculture workers in Pakistan, even when compared to Jordan, returning to Pakistan would mean that these families would be incapable of feeding their children.

It is true that life in Jordan has become hard, he says, but people here can still manage daily living matters at least. But they can only handle quotidian matters because they don’t own anything in Jordan.

This is not only because, as previously stated, they expend all that they earn on their families. For even the few families that could afford to own property are not able to because ownership is legally prohibited for Pakistanis.

While Shafiq was speaking, his nephew Mohannad stood behind him, leaning on the wall of the ‘arisha beside which everyone was gathered and sitting alongside, as an Emirati song played from his cellphone. Mohannad left school after the fifth grade and began working on the farm. As with all Jordan-born Pakistanis, whoever hears Mohannad speak cannot doubt that he is Jordanian. But during the gathering, he was communicating with his uncle and his other relatives in Sindhi, as Pakistanis speak their local language among one another, and not Arabic.

Since the vast majority of Pakistani Jordanians arrived from Balochistan or Sindh, the language they speak is Sindhi or Balochi.

According to Hasanein Heider, an official in the Pakistani embassy, this is one of the factors that deepens their estrangement from their country of origin.

Shafiq and his nephew Mohannad. Photos by Mohammed Zakaria.

Heider explains that in Pakistan there are many languages, each one particular to a specific province. These languages are dissimilar to the extent that their speakers do not understand one another. But, in turn, Pakistan depends on an official language, Urdu, which is unknown to the vast majority of Pakistanis in Jordan, who speak only their local languages. This further impedes their ability to adjust in case of their return to Pakistan.

The irony that Heider points to is that the difficulty of adjusting language-wise will remain even if they return to their local provinces. This is because, though they mastered their languages verbally, very few of them know how to read and write in the language.

The oldest migratory workforce

The director of the Tamkeen Center for migrant workers’ rights, Linda Kalash, reckons that the Pakistani workforce that began its emigration to Jordan in the mid sixties is the first migratory workforce in Jordan.

Thereafter, an outpouring began in the seventies of Egyptian and East Asian migrant workers.

Kalash points out that Pakistani workers are different from other migrant workers in that, for the most part, they don’t work as paid labor. Rather, they undertook a pattern of work on the farms in which their family members worked, and could get help from the workers of other nationalities who arrived in the seventies.

They are also different from other migrant labor in that they brought their families with them, and continued doing so. They came at a time in which there were no laws forbidding workers’ families from joining them, which is the situation now.

According to the latest detailed numbers from the Ministry of Labor, the number of Pakistani workers registered with the ministry was 3,205 in 2016, forming nearly 1% of the total of registered migrant workers.

Around 57% of Pakistani laborers work in agriculture, forming 2% of the total agricultural labor force in Jordan.

As for the percentage of the total number of Pakistanis, the numbers conflict. According to the administration of general statistics’ calculation for 2015, their number reaches 7,714, of which 41% is female.

However, Deputy Ambassador to Pakistan in Amman, Timour Zulfiqar, estimates their numbers to be between 15,000 to 20,000 people. He even points out that the number is most likely larger than that, and says that he thinks that those registered with the embassy don’t exceed 60 or 70% of the actual number of Pakistanis in Jordan.

According to Zulfiqar, Pakistanis have a big problem in regards to obtaining identification papers for their children in Jordan, because they are so often delayed in doing it.

“It happens a lot that a family comes with a fifteen year-old asking for a national ID and a passport for him. So we ask them: where was this boy sleeping for the past years?”

Zulfiqar adds that the Pakistani community in Jordan still values having a large number of children. Thus, in an average family there may be six or seven children. In some families, the number of children could reach 12 or 13.

According to Zulfiqar, the fact that Pakistani families are distributed across several regions and move with the seasons limits the small Pakistani embassy staff’s ability to count their numbers precisely.

The issue became more difficult upon the Pakistani government’s decision to require children of a day old to obtain a separate passport.

Heider says that this decision arrives within the context of a stricter policy undertaken by the Pakistani government in the last few years towards regulating the issuance of identity papers.

According to Heider, children used to be added manually to their mother’s or father’s passports until they reached sixteen years of age.

Yet, a few years ago, a new system of issuing children separate passports from birth was applied. This decision has meant even more expenses for the families.

7iber approached the Ministry of the Interior to request the number of Pakistanis obtaining visas, but has not yet received a response.

But the number of Pakistanis with [valid] visas is not a clear indication of their actual number in the kingdom.

According to many of those interviewed, numerous Pakistanis in Jordan have not renewed their visas. In the case of some children, they never obtained them in the first place, though the law of Residency and Foreign Affairs stipulates that they must request separate visas upon reaching sixteen years of age.

This is due to their inability to pay the visa fees, which reach 30 dinars a year per person.

And since the penalty for delay in renewing a visa is a fine of a dinar and a half for every day exceeded, Pakistanis say that many families accumulate fines of thousands of dinars.

Burdens ammassing to no end

In a camp of ‘arishas belonging to another family, Ali Al-Balushi (33 years old), sat with his relatives. They were discussing the recent general amnesty of 2018, which was issued after they were interviewed. The family was hoping that the amnesty would pardon fines for not renewing visas and work permits. According to Ali, the previous general amnesty, issued in 2011, pardoned them and enabled many others to correct their legal statuses.

But a big deterioration in the situations of farmers occurred during the last few years, which made the fines pile up once again: “One finds before one’s self two options: pay the fine or buy food to feed one’s children.”

Ali was born in Jordan. His father, “Khadim Hussein,” came to Jordan in 1976, when he was 14 years old, leaving Pakistan behind, which he says was “a wasteland” at the time. He came at the time in the company of his grandmother, his uncle and five aunts. The journey took eight months, because, like Zahra’s family, they had to stop more than once to work and gather the funds for the rest of the trip.

Ali, who is married to a woman also born in Jordan, and with whom he has three children, has not visited Pakistan before. “They say [Pakistan] is our country but we [only] see it on television,” says Ali in a clear Jordanian accent. “We are born here, we study here, we live here. I know Jordan more than Pakistan. I don’t know anything in Pakistan, while I know all of Jordan: its tribes and people and regions.”

Yet, according to Ali’s uncle, Gulajan Baluj (53 years old), Jordan, the only country they have ever known has dealt with them for decades by describing them as foreigners, despite their residency. They have to renew their visas every year, and seek work permits from the age of eighteen.

He notes that the law exempts those who have lived in Jordan for ten years from renewing their visa annually; and, instead, granted five year residencies

However, in the case of Pakistanis granted visas in accordance with their one-year work contracts, the visas must be renewed annually.

Gulajan came with his parents and four siblings in 1973, and settled down at first in Kharibat Al-Souq in south Amman. There, the men earned around 40 piasters a day by working in agriculture and construction. Like the rest, he has never visited Pakistan. Nor have his brothers, whose number grew to ten in Jordan.

Top photo: Ali Al-Balushi (mid left) and his uncle Gulajan Baluj (mid right) and two of their family members at a farm where they work in Dir Ala. Photos by Mohammed Zakaria.

According to Gulajan, residency fines are among the biggest concerns for Pakistanis in Jordan. He indicates that the reason for delay in renewing visas is not always due to an inability to pay the fees, but rather due to the difficulty of renewing work permits, which require a Jordanian guarantor to issue them — a prerequisite for residency.

The law of Residency and Foreign Affairs specifies a set of conditions that permit, on their basis, residency for a foreigner.

If these conditions are applied to the context of the Pakistani community in Jordan, there would be two cases that would permit a person older than eighteen to remain in the kingdom: if the person is employed, or a student.

The cost of an agriculture work permit is 520 dinars for the first year, and then 320 dinars each year thereafter. This is followed by a medical exam that costs 30 dinars. On top of the high cost of work permits, says Gulajan, there is the matter of obtaining a guarantor, which is no longer as easy a process as it was before.

Thus, the Pakistani worker finds that he must find a guarantor to issue work permits for him, his wife, and for his sons and daughters who have reached the age of eighteen. This can be, on average, 7 or 8 people in a single family.

Since the law puts restraints on the number of workers a guarantor can vouch for, and because these restraints are dependent on the space of the land that the guarantor owns, the type and number of fields therein, and if there are plastic houses or not, then the family is often apportioned between more than one guarantor: “half here and half there.”

According to Gulajan, if the farmers are associated with the guarantor via a partnership, then the Pakistani worker need not pay more than the legal fee. But if their relationship is simply a legal guarantee with the goal of obtaining a work permit, then the guarantor demands a sum to provide his legal guarantee.

At this point, Tareq, Ali’s nephew, enters the conversation. He says that the value of a legal guarantee usually fluctuates between 350 and 700 dinars.

He adds that, in addition to the high cost, finding a guarantor is not always an easy task for the Pakistani labor force.

This is because there is another migratory labor force that can pay more, namely Egyptian labor.

Kalash confirms this, saying: “the issued work permits of Egyptian workers has transformed into a business,” as the value of a permit has reached one thousand dinars. It is a “business” that exists primarily in the agriculture permits sector, because agricultural permits command the lowest cost compared to other permits, and obtaining them is easier.

Even after obtaining a guarantor, Gulajan says that a worker can become the guarantor’s captive if, as it often happens, the guarantor is late in seeking a work permit. In that case, fines accumulate for the worker and not for the guarantor.

The general amnesty of 2018 was issued days after our meeting with the families. It specified only an exemption for fines due to lateness in renewing visas, and did not include pardons for failure in seeking work permits.

And this, as Kalash says, is just “a temporary correction” to the still-existent malfunction. The reason for this dysfunction is the conflict between Labor Law and the Law of Residency and Foreign Affairs.

This is because a visa is not granted to a worker unless the worker has obtained a work permit.

Even though Labor Law restricts the right to request a permit to the guarantor alone, the guarantor’s failure to seek a permit means that the worker suffers the consequences.

It happens in some cases that workers discover that the business owner had not renewed their permits for years.

According to Kalash, the recent “amnesty” gave workers a respite of 180 days from the date of its implementation to leave the country or to rectify their situations, in case the workers wish to remain.

This means that “[the worker] must seek a work permit, and pay all of the fees for the work permits he had not obtained during the previous years.”

In addition to the limited practicality of seeking a work permit via a guarantor, Kalash points to another flaw: the nonexistent ceiling for fines accrued by exceeding a visa, which is the case for most countries in the world. But in Jordan, these fines accumulate for the worker ad infinitum.

The “Kuttab” School

As previously stated, a person above the age of eighteen is exempted from the obligation of seeking a work permit as a condition of obtaining a visa if he or she is a student.

But according to Zulfiqar, this does not help the Pakistani community in Jordan, of which only a small percentage can complete its scholastic studies, let alone university studies.

Schools in the kingdom accept migrant students on specific grounds. These grounds, says the director of the teaching administration in the ministry of education, Dr. Zeinab Al-Shawabkeh, forbid the enrollment of foreign expatriates’ children (non-Arabs), in public schools, and permit them only to enroll in private schools.

But this statement contradicts the current reality, as all of the Pakistanis we interviewed said that those among their children who are students study in public schools.

Al-Shawabkeh explains this by saying that many of the directors of education and school directors in the areas in which Pakistani workers are present disregard the application of the article banning foreign students from public schools in the interest of “acknowledging the human condition” of those workers.

The Ministry of Education is not unyielding in its role for the same reason: “a Pakistani worker works on a farm in the valley; how can I ask him to send his child to a private school?”

However, according to Al-Shawabkeh, when the children of Pakistanis enroll in private schools, the rules concerning school donations apply to them. These rules stipulate that non-Jordanian students must pay an annual sum of 40 dinars for primary school and 60 for high school.

According to the Pakistanis we met, the cost of school books is added on top of that.

Al-Shawabkeh says that, as in the case of any migrant pupil, legal residency is a fundamental condition for those students’ enrollment in these schools. This is a matter that the Ministry of Education cannot disregard due to security considerations.

There are no specific statistics about the education level of the Pakistani community in Jordan, but Zulfiqar says that the vast majority of them are “uneducated.”

The children do not usually remain in school for more than four or five years, after which they leave to work on farms with their relatives.

The issue is not only due to the financial cost of keeping six or seven children in school. There is also, as Zulfiqar says, the fact that schoolchildren are potential work hands that could be used on the farms.

Sumeya (32 years old), the mother of six children, confirms this, saying that children usually study until the sixth or seventh grade.

This is considered an improvement, as the situation was harder during her time, when the schools were fewer, and reaching them harder.

Sumeya was born in Jordan to a family that came from Sindh in the mid sixties. She says that she had many dreams in her childhood. One of these was for “us to live in houses and work in offices.” She adds, laughing: “and for me to become a doctor.”

But what in fact happened was that she left school after the second grade, got married in her early twenties, and had six children.

When we met her in a camp of ‘arishas belonging to her husband’s family in Dir Ala, her family consisted of her father in law, his two wives, and their children and grandchildren. The day we spoke to them was the day after a period of low temperatures, during which abundant rain fell on the area.

The dirt paths between the camps had turned into mud and children raced down them barefoot.

Sumeya pointed to her clothes splattered with mud, saying: “look, we harvest zucchini despite the mud, and yesterday we harvested in the rain. If we do not harvest, it will spoil.”

Sumeya says that children begin working in the farms around the age of thirteen. And with few exceptions, women also leave to work, while the older children take care of the younger children.

Sumeya points to her eldest child, Nisreen (9 years old), and says that she “takes care of her siblings. And I go check on her because we live on the same farm.”

Sumeya adds that the women who work in the farms undertake the housework when they return from the field. The entire responsibility for raising the children falls on their shoulders, which is not a simple task when living in the camps.

Sumeya says that the hardest times for her are the times of departure, specifically the transition period that precedes settling in a new place. This is when they begin dismantling the ‘arishas and fastening their possessions to move them and then arrange their things in the new place, all while the children “are in the sun, crying and screaming around us.”

What makes the matter harder is that this is mostly undertaken while still working on the farm.

Photos by Mohammed Zakaria.

Despite having left school after the second grade, Sumeya still remembers some of the little reading and writing in Arabic she learned at school, and which is enough to help the youngest of her children with their schoolwork.

In addition, she knows a little reading and writing in Sindhi, which she learned from her brother, who in turn had learned from his friend. This is a profound rarity among Pakistanis in Jordan, despite the existence of a Pakistani school in the Karameh region, which teaches its pupils to read and write in Sindhi and Urdu.

But the poor conditions of this school, and farming families’ difficulty in reaching it from distant regions limit its ability to be a broad influence on the Pakistani community. This is according to Mohammed Mushtaq (44 years old), who founded the school in 2002, and works as its sole teacher.

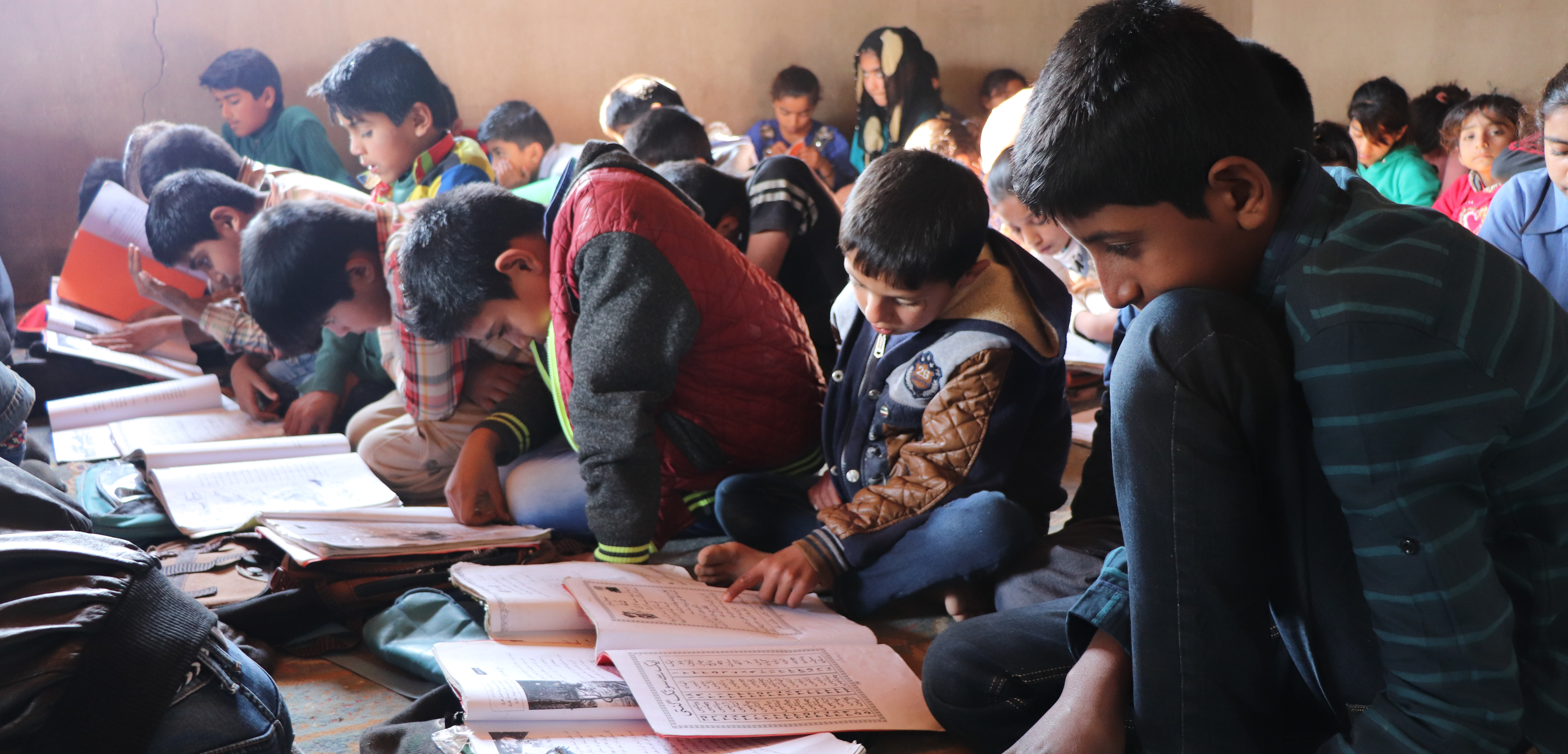

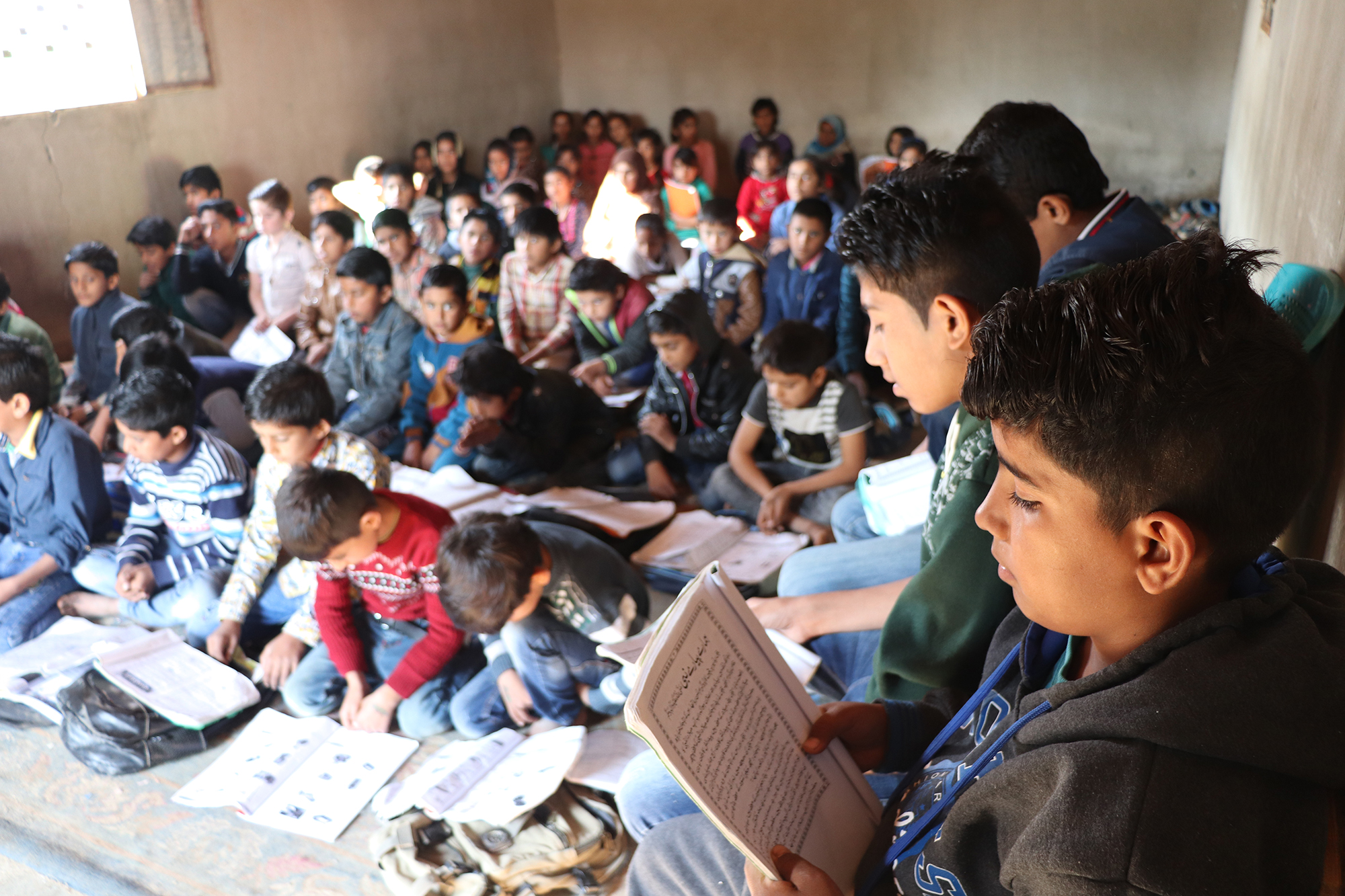

The school, which is located to the side of one of the area’s farms, less than two kilometers from the Karameh dam, is not truly a school, but more of a “kuttab,” since the building is basically a cement room of 9×5 meters with bare walls. During 7iber’s visit, there were 62 boys and girls between the ages of 5-16 years old. They were sitting on the cement floor because there were no chairs or desks.

Their seating was arranged by age group but with the separation of genders, so that the boys sat in the front, and the girls sat behind them.

The school day extends from eight in the morning to one in the afternoon, during which the children learn Sindhi, Urdu, and English, in addition to the Quran. Mushtaq says that the school is not officiated and therefore does not award any certificates or hold any exams. Yet, it maintains public school dates, namely the start and end of the school year, as well as school holidays.

It distributes the children in classes from one to ten, according to their ages and levels.

Mushtaq uses Pakistani curricula in his instruction. These were supplied by people coming from Pakistan when he was founding the school. He then copied them and distributed them to the children.

Mushtaq, who was born in Jordan, is one of the few teachers in the Pakistani-Jordanian community.

In 1987, his father sent him to Pakistan when he was twelve years old to study in its schools. He lived in his uncle’s house in Sindh for 14 years until he enrolled in university to study science.

But his father died in his first year of university, which forced him to cut short his studies, and return to Jordan to work in order to support his family.

Mushtaq and his students in their school. Photos by Dalal Salameh.

Mushtaq says that the idea of founding the school came to him when he saw that many children were not enrolled in school for reasons such as problems in their legal situation relating to residency, and sometimes due to the difficulty of assimilating in Arab schools.

Although a number of public schools in the area accept Pakistani students, some school directors refuse them, even when the school is the only one close to the student’s homes.

Mushtaq opened the school in 2002 in camp located beside a farm whose owner agreed to accept founding the school on its premises.

It was built nearly five kilometers away from its current location, and first housed 15 children, which grew to 40.

But he was forced to close it after seven years because the farm’s owner sold it, and the new owner asked them to leave.

The school closed for a year, and in 2010, it reopened in its new location, on a farm owned by a Pakistani person who designated a 200 meter piece of land to the school, and financed the construction of its classroom.

Mushtaq’s salary comes from tuition paid by the students’ families. In the beginning, tuition was 8 dinars a month. It is now 110 dinars a year.

Mushtaq says that the number of students is not consistent because pupils continue to move with their families. They come to the valley with the first rains, and leave at the beginning of the summer.

“Studies begin in September, but I receive new students until December. And in April they begin to leave.”

This, Mushtaq says, is another reason why Pakistani children apply to his school: public schools don’t accept students who do not enroll during their set dates,.

Mushtaq says that, in the beginning, payment of tuition was made only for the months in which the students attended. This was not sufficient for him. Thus, he says that tuition payment became annual, regardless of the number of months that the student actually attends: “The family knows that if they pay me, the school runs. [If they don’t pay], I’ll need to find another job.”

At the end of the school day, Mushtaq ends his workday. But since he is the father of six children whose ages range from 6 to 15 years old, he works in the fields for two or three hours, earning a dinar per hour.

Mushtaq teaches the students consecutively from the youngest to the oldest. He summons the students to his table one after another to listen to their reading, according to what time will allow.

He says that more than sixty children of different ages are present in the room to study different curricula at the same time.

“They exhaust [me],” but he tries at the very least to teach them to “read, at least.” He says that the families don’t aspire to more, and feel that it is an achievement, if realized.

Thus, what saddens him the most is the bright children who have dropped out during the past sixteen years, who he believes have left for the farms.

This is what made him think, some years ago, to develop the school by renting a house in the area, searching for other teachers, and lowering the tuition.

But he discovered that the matter was very complex, and that the resulting expenditures would be bigger than what the families were able to pay.

Hence, all that Mushtaq currently aspires to is for someone to donate chairs and desks for the students, fence off the space around the classroom and gate it, as well as create a shady spot so that the students can go outside during recess. He rarely allows them to go out, because he is afraid of exposing them to danger by going into the nearby street, or annoying the owners of the farm, which could lead to demands that they leave.

“They remain trapped in the room all day. But sometimes [a student] brings a piece of bread with him, so I let him go out on his own to eat it by himself.”

Mushtaq also wishes for a donation to ensure transportation for children living with their families in farms far away, since their families don’t have means of transportation.

The one room school from outside. Photo by Dalal Salameh.

Zulfiqar says that the embassy tries to support philanthropists who help the school. Some donations did indeed arrive from Pakistan, as well as from some urban Pakistani community organizations. The embassy took initiative by coordinating these forms of assistance.

But Zulfiqar points out that, in the end, “[their] mentality cannot be changed.” Thus, children raised in the farms are prepared mentally from a very young age to work in the profession of their parents and grandparents.

Therefore, when children make the decision to leave school after three or four years, the family welcomes it, because the family needs all the help it can get.

And what helps entrench this situation, says Zulfiqar, is the conviction held by the first generations of Pakistanis in Jordan that studying is not useful in the country, as most professions are already closed to Jordanian citizens, who suffer themselves on top of this from a high percentage of unemployment.

Ala’ Al-Baloushi (27 years old) is an example of this. He finished his studies in computer networks at Al-Zaytoonah University, and now works in an agricultural company.

Amid one of the family camps located in Dir Ala, Ala’ was sitting with his father, Mirkhan Al-Baloushi (65 years old), and a group of his brothers, uncles, and their sons in the ‘arisha that the family reserves for hosting,.

Mirkhan says, referring to Ala’: “I paid for [his studies] by the sweat of my brow, and he returned to work in agriculture. Is this not a shame?”

Mirkhan was sixteen when he came with his family to Jordan in 1970. His uncles had preceded them in Jordan by a few years, as they had arrived while “passing along the road to the Hijaz.”

Mirkhan had 16 children, three of whom died. All of his adult children now work in farms. The hope was that the university degree would secure a different destiny for Ala’, but that didn’t happen.

Five years after graduation, Ala’ concedes that he has no options beyond the farms. But the problem, he says, is legislation, which has expanded greatly over time. It has even made working in agriculture more arduous.

One such example is an edict issued 10 years ago that prohibited Pakistanis from seeking new driver’s licenses and banned the renewal of previously issued licenses.

This was confirmed by all of the Pakistanis we met. We contacted the Ministry of the Interior to investigate the existence of this edict, without receiving a response until now.

Mirkhan with two of his granddaughters (top), his son Ala’ (left) and Mushtaq the school teacher (right). Photos by Mohammed Zakaria.

Cars, says Ala’, are the backbone of farmers, as they use them to move their merchandise to the central market.

Because of the driving ban, farmers must rent cars to carry the merchandise. The trip from Dir Alla to the central market in Amman commands a fee of 50-60 dinars.

Alternatively, they can hire a driver to drive their cars, who charges no less than 400 dinars. With the low prices of vegetables, this means that a substantial portion of their profit goes towards transportation expenditures.

According to Ala’s cousin, Sultan (36 years old), this edict complicates not only working, but also the personal lives of farmers, who live in farms located in regions not served by an efficient transportation network. Many of them live in the interior areas, which public transportation mediums don’t reach. This formidably restricts their ability to move.

The problem heightens in cases of emergency: “It means that if a family member gets sick in the middle of the night, what can one do? I don’t live in the middle of Amman, [where] I can just call a taxi to reach me.”

“Not Pakistan and not Jordan”

The migration of most migrant workers in Arab countries, says Kalash, is called “cyclical emigration,” which means they come to these countries and then finally return to their homelands.

This does not apply to the Pakistani workers in Jordan, whose emigration is of a kind of “eternal emigration,” even though this is not reflected in their legal classification in Jordan.

Mirkhan says that Pakistanis feel a bitterness, as they see that they have been active contributors to the Jordanian economy for decades.

They worked in the valley region at a time when it was all “trees and forests and beasts and hyenas and pigs. The valley was desolate and chaotic. It was a path for shepherds and wanderers. There was no one who could walk from here to Karameh.”

Mirkhan says they worked in these conditions and spent all what they earned within Jordan, even though they came with the intention of returning to their country.

“When people emigrated they remained here in this situation. They would say today I will return, tomorrow I’ll return, next year I’ll return. They never returned, and didn’t benefit from being here and didn’t benefit from being there.”

As Sultan says, this feeling, that there is no way of returning, is not only due to the fact that they did not secure houses or investments in Pakistan. There is also, Sultan says, a case of cultural separation that deepens generation after generation.

Almost all members of the first generation have died, while most of the second generation of Pakistanis arrived in Jordan with their parents when they were children, and have never visited Pakistan.

This means that the vast majority of the Pakistani community in Jordan consists of people who have never known any other country besides Jordan.

And these people, says Sultan, assimilate more and more deeply into Jordanian culture. As Zulfiqar says: “the one thing that indicates that they are Pakistani is the clothes their women wear.”

Sultan offers a simple example of this, displayed by the kind of art that they consume. He says that he remembers when there was a generation that loved to watch Pakistani movies and listen to Pakistani music, but now the new generation “only watches Syrian and Egyptian shows, and listens to Arabic songs. This means that maybe you can find someone who listens to Pakistani music among the people born in the mid eighties, but it’s much harder to find people born in the nineties [who listen to Pakistani music]. They don’t understand Pakistani songs.”

Sumeya says that most of the dishes that she cooks are Jordanian foods, except in the case of weddings, in which the rice is still cooked in the Pakistani way.

But even weddings experienced change in previous years. Sumeya remembers when wedding parties were held in the Pakistani way, and the bride wore a red wedding gown, and the groom wore a traditional Pakistani thobe, but now “the bride wears a white dress and sits on her throne, and we get a big tent and seats like the Jordanians.”

A group of Pakistani girls in Dir Ala (right), and Zahra at her home (left). Photos by Mohammed Zakariya.

Zulfiqar says that Pakistan is open to all citizens who want to return, but that Pakistanis in Jordan live “in a deadlock,” because on one hand, they cannot return, and on the other hand, remaining becomes more difficult, year after year.

According to Zulfiqar, Pakistanis carry some of the responsibility for this hardship: “the mistake they made was that they cut their roots with Pakistan (…) and they did not maintain their relationship with the places that their families came from.”

Zulfiqar recounts many cases of Pakistanis presenting requests for identity papers to the Pakistani embassy, only to find out that they did not have the documents, or that they had very old documents that were no longer valid as verification.

And when the authorities inquire about them in the Pakistani villages that they came from, in order to verify their identities, “we find that nobody ever knows them there.”

Zahra says, crying, that she does not want to return to Pakistan even if the chance was available to her, as her parents, uncles, aunts, and all of the adult relatives that she left behind have died, and her return would have been only to see them.

After fifty years away from that land, she says, “here is our Pakistan.” But Mushtaq says that the situation is, in reality, that “we are in the middle. Not in Pakistan and not in Jordan.”