When they were children, Ahmad and Shaker never thought that “Adnan and Lina,” a TV show broadcast in Kuwaiti dialect, had anything to do with Japan. Perhaps this piece of information was irrelevant for two young boys enamoured with the pretty colors on the screen, a thrilling story about a post-apocalyptic world set in 2008, and a strong and cheerful hero adventuring with the aid of his friends.

But the two boys, who today are admins of the “Ask me about anime” Facebook group, now know, from watching a large number of cartoon series, that that show, like similar others, is known by a different name: “anime.” As for the show they were discussing, it was dubbed and poorly cut from the original.

The origins of anime, which, in Japanese, means animation, can be traced back to the history of animation cinema. The oldest Japanese animated film ever shown dates back to 1917. Researcher Maria Roberta Novielli explains that the origins of anime can be traced back to Emakimono art, which arose in the Middle Ages in Japan.

At the time, stories were narrated via drawings or handscrolls, in addition to numerous other means of storytelling across history. Some examples of this are Kamishibai (the art of storytelling using pictures), or Bunraku (puppet shows).[1]

Since the birth of anime, the Japanese government has tried to control and guide it. In 1911, it established what was known as the Committee for the Popular Educational Enquiry, which was concerned with all things recreation. This committee directed, or funded, many anime productions on numerous occasions. It did so during disasters and wars in order to broadcast the government’s version of “national spirit” to the people, or its vision of Japan, before the world.[2]

“Otaku” refers to a person so passionate about something or a talent to the degree that they do not leave their home in order to keep practicing it. This word has become, in popular cultures of many countries, including Jordan, indicative of a person obsessed with anime and manga (manga are Japanese comics).

For this report, we met with a group of Jordanian Otakus to speak with them about the anime and manga community in Jordan. We spoke to them about the beginning of their transition from watching dubbed anime to original anime shows. Also, about Facebook groups for people interested in anime, and their activities, such as reading manga and authoring it.

Watching Anime and Reading Manga in Jordan

Shaker Al-Lahaam (22 years old, mechanical engineering) credits internet culture for his knowledge of anime. Like the rest of his peers, he watched cartoons on TV until the internet introduced him to shows of Japanese origin and provided him with platforms to watch his favorite anime shows.

The first anime Shaker watched was Naruto. “It was the first thing I watched passionately, episode by episode and week by week. I caught up with it when I finished the first part (2006) when [Naruto] was small, and I continued until he grew up (Naruto Shippuden).”

According to Ahmad Abu Ghosh (24 years old, medical engineer), the difference between the original version and the dubbed version was vast. The censorship in the Arabic version affected the content because the dubbing center believed that, due to cultural differences, certain concepts were not appropriate for Arab audiences. For example, “In Dragon Ball Z, Goku died 7 times, and when he returns (because he is immortal), the dubbing explains that he was in the hospital, despite the fact that you are seeing his heart exploding.”

Shaker believes that the Syrian center for dubbing, Azzahra, has a set of values that it wants to instill in Arab youth through its edits of the original shows. For example, the company hid the body of Ran, a character in the anime “Detective Conan: (Case Closed).” This is not to mention according to Shaker, the ridiculous voice acting in the Arabic version.

Many Facebook groups, arising from internet culture too, formed a connecting link between Otakus in Jordan and provided a place to exchange experiences. Maha Shati (25 years old, bank employee) says that, in 2008, she and a group of her friends established a group called “Anime lovers in Jordan” on Facebook.

“We made the group when we were still in school and 15 years old. The idea for the group was for it to be a place to gather people in Jordan who understand anime and love it.”

In her opinion, many people don’t know that there is an original version of what they are watching on TV.

According to an admin of the “Ask me about anime” group, Isra’ ‘Arar (24 years old, university teachers’ assistant), memes and other entertainment represent most of the content on anime and manga Facebook groups and pages. Discussing manga and anime series that have not yet ended comprises a big portion of the discourse. By Abu Ghosh’s description, this ongoing conversation consists of predictions of anime or manga series’ future plots as well as analyses of recent events in shows.

According to Maha, the discussion extends also to Japanese culture in general, and questions about Japanese language and games.

By Maha Shati’s estimation, which is accepted by the rest of the Otakus we spoke to, the 15-25 age group forms the biggest part of these groups’ members. Shaker Al-Lahaam and Ahmad Abu Ghosh indicate that anime and manga’s largest targeted demographic is located between the ages of 13-17 years. This becomes most evident when you note that manga and anime are not only categorized by genre (e.g. action, romance, comedy, sports, gambling, slice of life), but also by targeted age groups of readers/viewers.

Shaker continues: “The Japanese government heavily investigates i studios and with anime shows. A guy [between the ages of 13-17] will watch anime and his personality is going to be formed according to that.”

Abu Ghosh explains that anime shows are broadcast in Japan at different times according to the ages of the targeted viewers. “For example, an anime like Attack on Titan [17+] is shown at 10 or 11 in the evening, to guarantee that kids are asleep.”

But most of manga and anime’s audience in our region is no longer controlled by the restrictions of TV broadcasting, thanks to the internet. According to Isra’ ‘Arar, Arabic websites that provide translated anime shows and manga represent the main source for Otakus in the region for most, if not all the works issued recently in Japan, as well as the classics.

In the anime industry report of 2017 issued by the Japanese Animation Association, numbers indicate a lack of broadcast licensing contracts for anime in the Arab region.This is despite an abundance of manga and anime content on the internet.

According to Shaker, it’s worth mentioning that readers of manga in the Arab region have limited options to get ahold of it. They can either order it from online stores or buy it from rare shops in Jordan.

Visitors at Saudi Arabia’s first Comic-Con in Jeddah, 2017. AP.

In addition to online activity in Facebook groups, many groups are calling for more activities beyond the internet. These are called for on a small scale (such as exchanging shows and books or selling products), or on a larger scale in an imitation of Comic-Con. By Maha’s description, Comic-Con is a convention that includes many activities like video games, game card competitions, cosplay competitions, Origami, and much more.

But, according to Isra, ’“[the success of Comic-Con’s Jordanian counterpart] is limited because of the lack of managing experience in regards to events of this size. In my opinion, it will take time to resemble global events.”.

Manga and Anime as a Local Product

Shaker Al-Lahaam and Ahmad Abu Ghosh believe that manga and anime are distinguished from comics and cartoons around the world by certain qualities. For a start, the word “anime” denotes a show produced in Japan. In addition, anime, according Al-Lahaam and Abu Ghosh, is a special style of drawing, storytelling, and character design.

According to Shaker, the broad spectrum of anime gathers together many heroes, some of whom have super powers, while others are humans, like us, who suffer from the same things we do in our daily lives. Shaker adds: “90% of anime shows feature a hero with an impossible goal in relation to his abilities.t that moment [at the beginning of the show], is impossible for him to achieve that goal. What is the great thing you are going to do to achieve your dream? This is the story.” Shaker continues: “What does Spider Man want to achieve? He wants to save the city. It’s a continuous war between good and evil. That’s it. While in anime, it’s about achieving one’s dreams.”

But Diana Al’Abadi, a Jordanian manga author (32 years old), has a less radical opinion on the matter. She says: “I don’t like to differentiate between them. In my view, manga, comics, and graphic novels all fall under the same umbrella called the art of telling stories using harmony between drawings and words.”

Diana’s relationship with anime and manga began during her adolescence, when she got her first book of manga at college. She graduated in 2009 from University of Jordan with a degree in architecture, but immediately pursued work as a narrator of “picture books” according to her. “My goal, since my teenage years, was to share characters and stories of my imagination with people around me. I insisted upon not committing to any job outside of this field,” says Diana.

In order to achieve that, Diana worked during her studies on sharpening her skills by practicing drawing stories she had written previously. “I didn’t like manga, and I had never read one before because I saw that anime was better and stronger and had music. I didn’t know that my decision to draw stories would open a door for me to a world in which I have a house and a job and a journey.”

After she began learning how to draw and had sharpened her skills, Diana did freelancing work as a character designer for three years. In 2011, she began to publish episodes of her own manga “Grey is…” She used personal funds and published the episodes on her personal site.

“In 2012, the story was published in Spain in Spanish. Three of my stories were published in books and magazines in Japan. A short silent film was produced from one of my winning stories in the global silent manga competition,” says Diana.

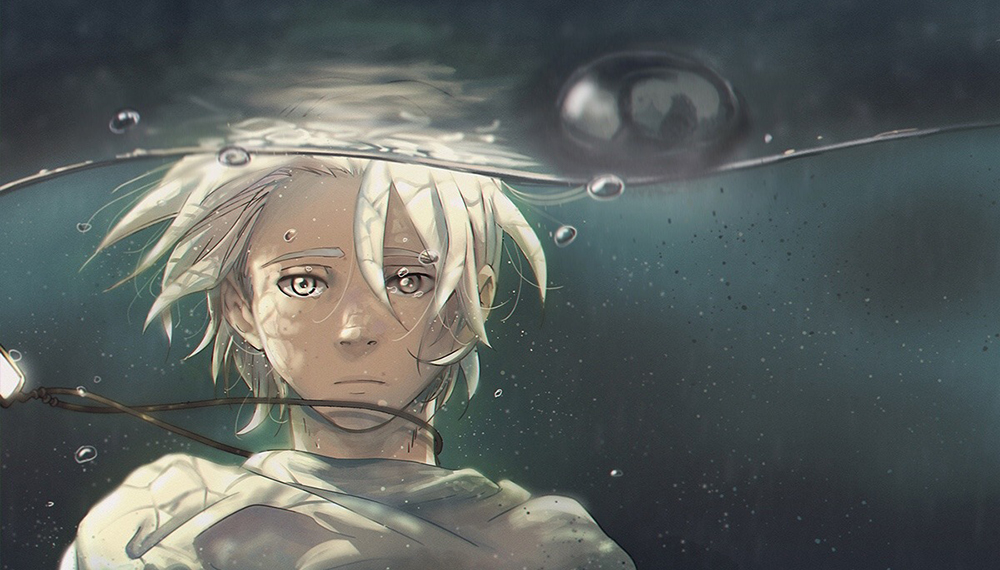

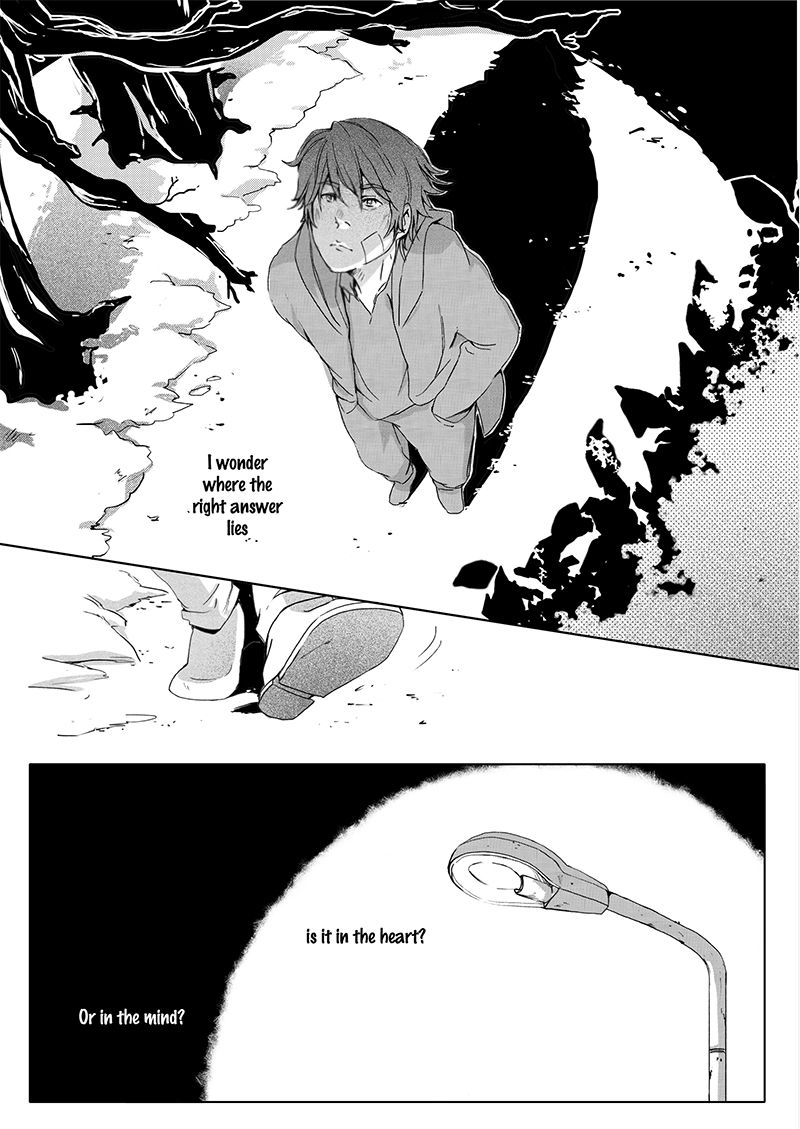

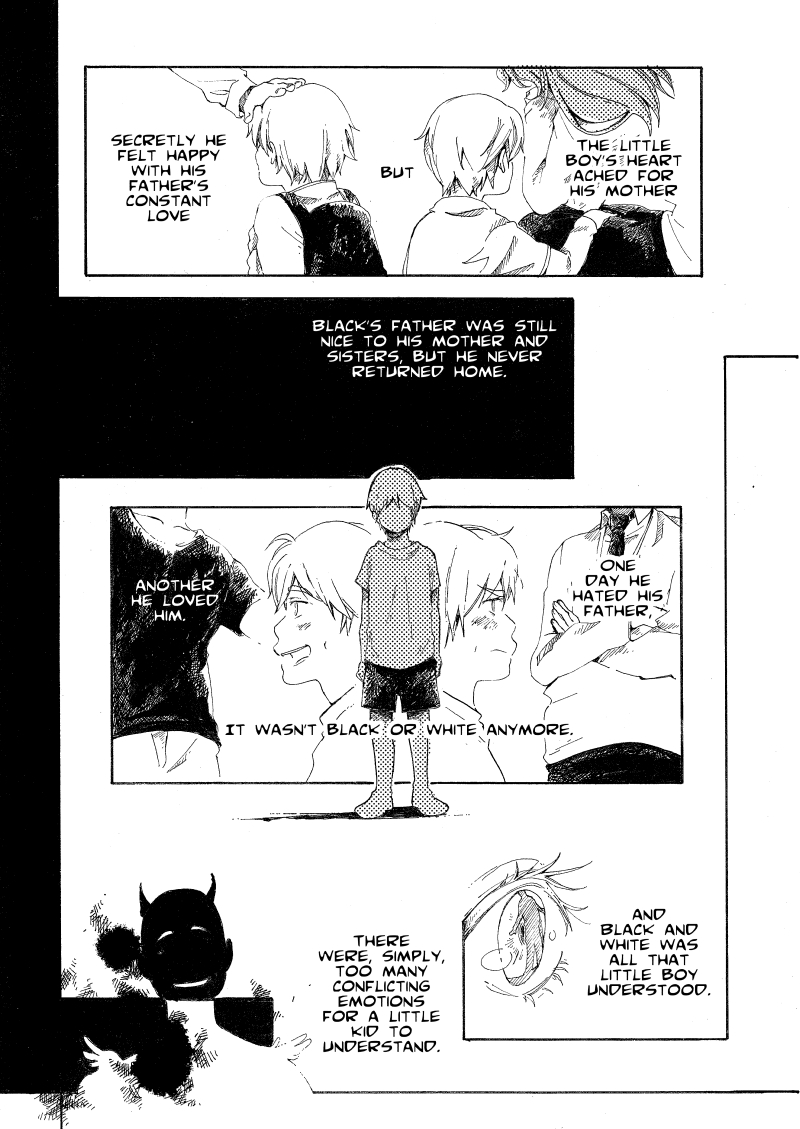

Her manga, “Grey is…” recounts the story of the friendship of two people who represent the harmony and conflict between the heart and mind, according to Diana’s description. “The story is about two boys, one is emotional and named Black, though he is Albino with white hair, and his clothes are white. The other one is rational and his name is White; and like his friend, his outward appearance,(including his hair and clothes)contrast with his name. They have been friends since childhood, which was not easy for either of them, forcing them to choose one road to deal with life’s difficulties. They chose to distance themselves from the middle ground, or as it is called “greyness,” which influenced their lives and their psychology in their childhood and adolescence.”

As Diana describes, the story deals with the subjects of domestic violence and depression, and with family relationships that search for shared ground between the heart and mind.

From Diana Al’Abadi’s manga “Grey is…”

Diana Al’Abadi’s manga is still the outcome of her own work solely: writing, drawing, producing, distributing (hard copy and online). She works daily, without breaks, between 6 and 14 hours.

“When I am travelling or publishing books, this workload lessens, but it continues every day. The average number of pages [that she completes] personally varies between two pages a day to five.”

Diana expects to continue publishing “Grey is…” for another few years. She says this is due to the high demand for manga and anime in our region, and her manga series’s large audience.

Diana indicates that the spread of the idea of authoring manga in the Arab region has been growing , as witnessed in the increasing number of Arab-produced mangas, of which there are many For example: the story “13:05” published in the magazine “E3sar,” written by Amani Badran, and “Odis” by Sara Muhammad, Enios by Firas Al’Amireen, in addition to “Siwar Athahab,” by Qais Sudqi, and drawn by Akira Himikawa. But this spread, according to Maha Shati, is still in the beginning stages, and needs care and support.

Moreover, the number of youths who gradually grew their knowledge of Japanese language by watching anime, reading manga, or by studying it formally has led to them becoming translators on platforms for Arabic anime broadcast, according to Shaker and Ahmad.

Isra’ ‘Arar believes that the manga and anime scene in Jordan and in the Arab region is missing the proclamation that it is suitable for a wide spectrum, which extends from childhood to maturity. According to many studies, the pages of manga or anime episodes represent a space for philosophical and societal discussion inspired from what the heroes of the stories face.

-

References

[1] Floating Worlds: A Short History of Japanese Animation, Maria Roberta Novielli, CRC press, 2018, p. 1

[2] Ibid. p. 6.