By Ezzedine Al-Natour, photography by Hussam Da’na

Translated from Arabic by Orion Wilcox

(This article first appeared on 7iber in Arabic).

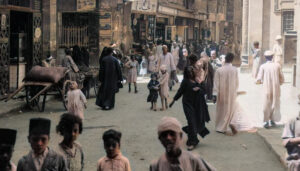

Anyone driving through the Balqa Governorate near the town of Madi will notice the makeshift houses clustered along both sides of the highway. These are—for the most part—the homes of Egyptian laborers working on nearby farms.

The encampments are spread out along the highway connecting the villages of Deir ‘Alla. They are in fact small villages in their own right, built by Egyptian workers in areas lacking access to the most basic amenities. Reminiscent of the slums that stretch out around the mega-cities of Egypt, the houses here are a hazard to whoever occupies them.

Most of the residents of these encampments work as day laborers, collecting pay only for the number of hours they are able to work each day—about a dinar or a dinar and a half per hour worked. They came to Jordan by way of middlemen who procure work permits for a fee in exchange for allowing their clients to work wherever they want in Jordan. The middleman remains as worker’s guarantor for the duration of his time in Jordan.

The laborers build their homes with raw materials found around the farms where they work: plastic from irrigation pipes, empty bags of fertilizer, and cardboard. Sheets of tin and plywood fill in for doors and roofs.

The cost of constructing one shelter can be as much as 200 dinars, split among the eight or so people that occupy the compact space.

The encampments lack most basic amenities other than electricity, provided by extension cords lying in tangled piles between the houses and connecting to nearby grocery stores or neighborhoods—the cost of electricity runs around 20 dinars per month. Water is purchased and stored in containers near the houses and the workers have dug out a primitive, exposed sewage system running between the houses.

The encampments date back to the late 1980’s, according to Egyptian migrant worker Shaher Abderahman. He first moved into the encampment in 1993 when there were only a few makeshift houses on one side of the highway but says that soon after he arrived the encampments grew into their current form.

The laborers prefer these encampments to other housing options because they are close to the farming land where they work—and they are well known to the farm owners who come here to hire day-laborers, says Abderahman, who is originally from the Egyptian area of Sohag. The benefits of living in the encampments have made it difficult to leave, despite the multiple attempts of the owner of the land to evict the workers, he says.

“Our situation is just as you see it. We can’t leave here and live anywhere else—the money we make barely covers our daily expenses,” says Rashad Mahdi, who came to Jordan in 2004. “At the end of the month we might send 100 dinars to our family in Egypt,” he adds.

The laborers wake up at 5 A.M to prepare for the day’s work. “I came here to work as a tractor driver,” says Salim as he dips his breakfast cake in a cup of tea. “I drove tractors when I first got here but everyday I had a problem with the police. They didn’t let me work on a tractor. There are people who came here 30 years ago and their situation hasn’t changed.”

Most of the workers living in these encampments come from the Egyptian province of Sohag—or the “Egyptian capital of poverty” as they refer to it. Perhaps this explains why they accept living in these makeshift houses and in these conditions.

Poverty knows no age. Above is 60-year-old Amm Ahmed who responded to all of our questions by saying “al-Hamdullilah ‘ala Kul Hal” [Thank God for everything.]