By Lara Darwazeh

Many factors separate a country from another. War devastations and political instabilities add to this distance one perceives. Working against such a partition is the human and cultural connection between people and cultures. This is the feeling I had, as I was leaving a food and handicraft festival last week in the Jordanian city of Ramtha.

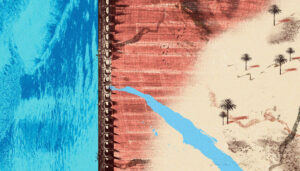

Situated in the far northwest of Jordan, Ramtha is only 23 kilometers from the Syrian town of Daraa. The two towns always had a strong trade relationship as well as family ties. When I got a call from a friend inviting me to a meeting of Syrian women affected by the war and are now cooking and selling their Syrian dishes to support their families, I was very keen to go.

The event in Ramtha was organized by an international NGO, working to bring together Jordanian women and Syrian refugees. It was a smaller event connected to a larger Olive and Rural Produce Festival.

One Syrian woman, Fathieh, told the story of how she fled to Jordan after a rocket hit her house in Daraa, leaving her son with a debilitating injury. Her daughter followed them soon after.

She stood behind her counter selling her own homemade remedies for various skin conditions, something she had learned from her father and grandfather when she was still in Daraa, where she had regular patients. She sells her products from home now.

Um Qasem is from Syria but now lives in the city of Ramtha. As she sold fried Kibbeh, her smile never left her face. One difference between the Syrian Kibbeh and the Jordanian one, she explained, is that they use no flour but semolina and eggs instead, which adds to the crunchiness of Syrian Kibbeh.

Um Rana described further the differences between both Jordanian and Syrian cuisines. There are many intricacies that go into the Syrian kitchen, like the red chili molasses. “We dry chilies and preserve them in oil to stuff and pickle eggplants with” she explained.

Kibbeh, it seems, has many themes and variations in the Syrian kitchen. “There are sixty types of Kibbeh in Aleppo,” Um Rana told me. “We grill it, fry it, boil it in yogurt. And finally there is the ultimate Kibbeh: Kibbeh Safarjalieh,” she passionately explained. Cooked with Quince (English for Safarjal) the dish combines both sweet and sour tastes; a typical Aleppine tradition.

Kibbeh, it seems, has many themes and variations in the Syrian kitchen. “There are sixty types of Kibbeh in Aleppo,” Um Rana told me. “We grill it, fry it, boil it in yogurt. And finally there is the ultimate Kibbeh: Kibbeh Safarjalieh,” she passionately explained. Cooked with Quince (English for Safarjal) the dish combines both sweet and sour tastes; a typical Aleppine tradition.

Across the tent, Jordanian Um Mohammad particularly stood out amongst the women. She had a striking Bedouin dress and voiced loudly the lack of initiatives and projects available to the women in the association she runs, The Women’s Hands Charities Association. “Nobody pays attention to us,” she explained. “There is no support”.

“I understand these women’s frustrations,” said ILO Coordinator Ms. Maha Kattah. “The women need to be trained to run small businesses and learn how to promote and manage their finances”.

Having spoken to some of the women from the cities of Daraa and Ramtha, I came away from the festival with a feeling that these women needed a lot more support to market their work. They all brought admirable and varied resources to the festival- their resilience resonated with Fathieh’s sentence “life continues and we have to keep going”.