The promise of a series of children’s books claiming to teach compassion toward disabled people is immediately broken for Rawan Baybars as she leafs through its brightly illustrated pages. In the Jordanian books-financed by the Dutch embassy and international NGOs-she finds an appalling and insensitive view that fixates on the misery that the intellectually disabled supposedly inflict on their families.

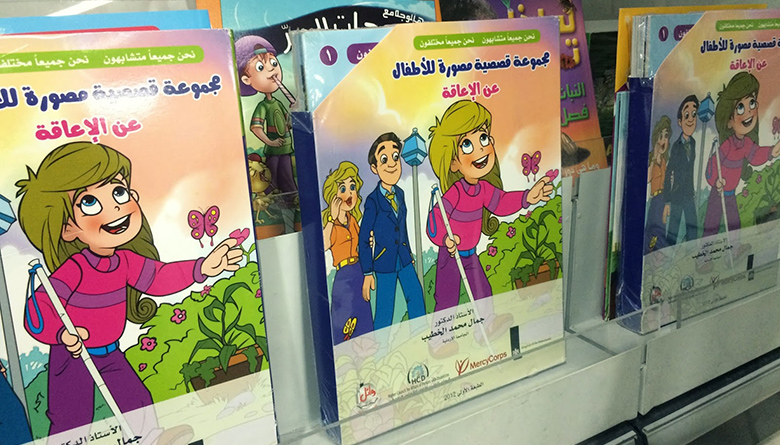

I recently came across an illustrated children’s book series on the ‘handicapped’ in one of Amman’s shopping malls. Despite my reservations at the use of the term ‘handicapped,’ I was naively happy to see this attempt to explain special needs to other children. I must have flipped through the books for less than five minutes before I found myself staring at the pages in disbelief.

The first story I read was, ‘My Son, Salem’, featuring a child who has Down syndrome. It was hard to miss the many negative images and stereotypes in the book. Salem’s features are negatively described in detail, as if calling upon children to focus on physical appearance over other personality traits. The authors describe Salem with the following catalog of features: he ‘has a small head, he is cross-eyed, he has a weak brain and weak muscles; has a round face, and he is slow.’ Salem, who is still just a child, is immediately judged as physically and cognitively deficient.

The story might better have instead encouraged children to think beyond stereotypes, and focus on how a child with Down syndrome is happy, sociable and loves to dance.

At a time when people with Down syndrome are successfully assimilating in their societies, taking on academic positions and artistic professions, our Arab communities are still reinforcing negative stereotypes of people with special needs; the book series discussed here is a case in point.

The series could have taken inspiration from outstanding people with Down syndrome, such as Sujeet Desai (an inspiring musician who plays four instruments), Christian Royal (an exceptional young potter), and Tim Harris (a restaurateur who graduated from New Mexico University with certificates in Food Service and Restaurant Hosting).

This does not mean, however, that we should undermine the challenges that people with Down syndrome and their families often face, or over-romanticize their struggle. The goal, as claimed by the series’ introduction, is “to help deconstruct misconceptions and combat stereotypes in Arab societies about children with handicaps.” Therefore, the series should have at least portrayed how those born with Down syndrome are loved by their families; and how their families are relentlessly fighting against society’s negative perceptions of children with impairments. They are in fact fighting against the same stereotypes that the series unfortunately end ups reinforcing.

The series’ portrayal of the attitude of family members of children with impairments is problematic to say the least. After a couple finds out they are pregnant with a child with Down syndrome, we see the father moaning as he enters the doctor’s clinic, while the mother is lost in her sadness. What the doctor is quoted to have said to the parents is disastrous: ‘he said our son will live in a state of torpor; he will forever be a burden; that we will wish he had died.’

The stories focus on negative images and perceptions in so much detail, which make them stick in the children’s minds.

The above words, believe it or not, constitute ‘medical opinion’ on Down syndrome in the series. In another page, we encounter the following text: ‘We felt unsteady in the beginning of the journey; our life was coming to an end in front of our eyes and we were overwhelmed by a scary sense of despair and pessimism that made the young and old weep.’ The text thus instills in children’s minds that having a family member with Down syndrome is a depressingly huge burden that leads to distraught weeping. […]

‘My Son, Salem’ is full of negative statements. In the final segment of the story, we encounter the father watching Salem as he runs towards him. The father utters the following statement.

‘Why is everyone preoccupied with the future? Will he really be better after proper training? This is what is worrying. What about brothers and sisters? My son is not a heavy burden now.’

The father remains uncertain of his son as he asks if he will ever be better. His words also emphasize that Salem remains a burden, even if not a heavy one.

The second story I read in the series is, ‘Bassem’. It is about a child with autism whose story is narrated by his sister, Wafaa. In Arabic, ‘Bassem’ means smiling, but the boy in the story is portrayed as being constantly grumpy. This is how the author describes autism through Wafaa’s words.

‘My brother has a condition called autism. His movements resemble those of prayer: he moves his head backwards and forward, and flutters his arms while murmuring. His training is a struggle and his sleep is worship.’

There is a common proverb in Arabic that translates as follows: ‘The sleep of the tyrant is worship.’ How is it possible that the author borrows such a proverb to describe a child who has autism in a children’s book?!

In the story, Bassem’s family members’ feelings towards him are mostly negative, as they are unable to comprehend the signs of his deferred social skills for example. On page seven of the book, we encounter the following statement:

‘My father is sad and deflated. He is overtaken by anger whenever he sees him. He complains to God. But my dear mother calms him down from time to time, saying ‘it is a hardship that will go away.’

In one dialogue, Wafaa talks about Bassem with her friend, Laila. She complains about having to bear the responsibility of her brother, and about how all her mom’s attention is directed to him. ‘I can not deny that I am bothered….He is my brother and I love him, but he is constantly causing us problems,’ Wafaa tells Laila. It is clear that Wafaa’s love for her brother is dubious and conditional on Bassem being her biological brother.

In another instance, one of the neighbors asks Bassem’s mother if there is a cure for autism. She replies by saying that there is no cure, and adds, ‘some children improve by time, but there is a huge number of them who remain dependent, and in need of continuous care. I hope that Bassem is one of those who improve.’

‘Improvement’ here is not portrayed as an outcome of training and rehabilitation, but as something that happens by chance. This portrayal reinforces negativity, passiveness and deficiency.

I believe that religious discourse was additionally employed to reinforce negative perceptions of impairments. In response to the neighbor’s prayer for Bassem, the mother puts her hands on her head and calls upon God’s wide mercy. Her body language again reinforces the sense of passivity that dominates the text.

As a sister of a person who has autism myself, the last thing I needed was yet another story that portrays my young brother in such a negative light. We had enough of those stories growing up. There are many repercussions for having a special needs member in a family, but at the same time they are a source of joy and pride. My brother creates a challenge for the family, and his slow and steady steps towards independence give meaning to life. His small achievements bring immense joy and celebration.

I know that publishing this series on disability for children was well intended and meant to raise awareness. But we have to admit that the writing was deeply harmful on a psychological level. The stories focus on negative images and perceptions in so much detail, which make them stick in the children’s minds. The endings were weak, and incomparable to the overdramatic statements made. (…)

Finally, it is important to address the conditions of production of the series discussed here. First, the author is a professor at the University of Jordan. If these are the views about special needs that are being promoted at the university, then we are in a crisis. It is quite obvious that academic credentials are not enough to write about such sensitive topics for children. Children literature and the wide array of texts and illustrations that it encompasses is an established genre with a significant psychological depth. Children’s books are formative and can inscribe ideas and views that are difficult to erase later.

Secondly, Jordan’s Higher Council For Affairs Of Persons With Disabilities sponsored the series, and Prince Zeid bin Ra’ad (the current United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights) wrote its introduction. Was the prince too busy to read the books before introducing them? Or did he introduce this work not realizing the misconceptions and disastrous ‘educational’ messages it promotes?

Thirdly, both the Dutch embassy and the global humanitarian aid agency, MercyCorps, have supported the series. When I contacted the Dutch embassy inquiring about their funding of this series, they expressed ‘their sadness about what happened, and their support of the rights of people with impairments, in addition to their belief in the complete assimilation of those with special needs’. But, they stated that they are not responsible for the content of the series, and that they do not interfere in the final work produced by their project partners.

Foreign funding agencies often claim that their projects are meant to help the Jordanian society and work on its development, which includes spreading progressive views and combating of regressive ones. Yet, the lack of responsibility expressed by the Dutch embassy indicates that they are not concerned at all by human rights violations committed by those they fund. Now we have to wonder, what is their criteria for choosing ‘partners’ who receive such lucrative grants without any oversight over the final product?

The only positive thing about this series is that it is over-priced; it costs 27 dinars (38 US dollars). I hope that no family invests this much money on such an unbefitting series, which I believe needs to be withdrawn from the markets.