Neoliberal urbanism, in the simplest terms, is the privatization of development, in which such projects are driven by market-driven logic, with profit as the essential goal. Neoliberalism, as an economic system, typically diminishes the role of the State, but as Jamie Peck argued, the “ideological shape of the State has not changed as much as neoliberal reformers would have us believe.”[1] The Jordanian State, is indeed not diminished, but rather, enjoys a certain elasticity, and the ability to, under the premise of reform, reinvent its roles and responsibilities in the project of development. Consequently, several neoliberal development projects in Amman—among them The Limitless Towers and The Royal Village—are curiously the product of a public-private partnership between the state and various private investors.

Neoliberal urbanism in Amman has produced a variety of shopping malls, upscale apartment buildings, and spectacular high-rise towers, all projects of imported modernization schemes. These projects have, however, “given way to a landscape marred by empty buildings, gaping holes and the skeletal remains of speculative projects gone bust.”[2] In the meantime, the political economy of wealth and power in Amman is such that the oligarchs and royal elites do not suffer the economic consequence of these failures, able to “ensure themselves a bailout when speculative bubbles burst.”[3]

Limitless Towers and The Royal Village are example of failed neoliberal minded development ventures. Each project is in a varied state of incompletion, the result of a system of ruination in which incompleteness or project failure is not—as would otherwise be expected—directly linked to economic loss. The process of neoliberalization in Amman in fact ensures financial success for the State and its oligarchic network, regardless of their failure, deeming them desirable and profitable due to the State’s appropriation of public and privately held lands as “domain,” in turn selling the properties to private developers at a premium. Land on the outskirts of the city is continually appropriated as state domain, a dispossession of privately owned lands by the government, also sold for private development.[4] Neoliberal failures, such as these projects, are precisely why Najib Hourani argues that neoliberal market strategies—particularly market- driven urbanism—must be subjected to a context-specific evaluation. Broadly and loosely applied, the process of neoliberalization will likely, as is the case in Amman, fail.

The Royal Village

The Royal Village, designed as a complex for luxurious urban living, was sited approximately five miles from the sixth circle in Amman, which is the location of the Jordan Gate Towers project. The land for the Village was acquired by the Greater Amman Municipality in 1984, and used as an industrial space until 2004, when GAM was given a purchase offer by KIPCO to develop the land.[5] The Royal Village was initiated first, followed, in rapid succession, by the Jordan Gate in 2005, and Limitless Towers in 2008.

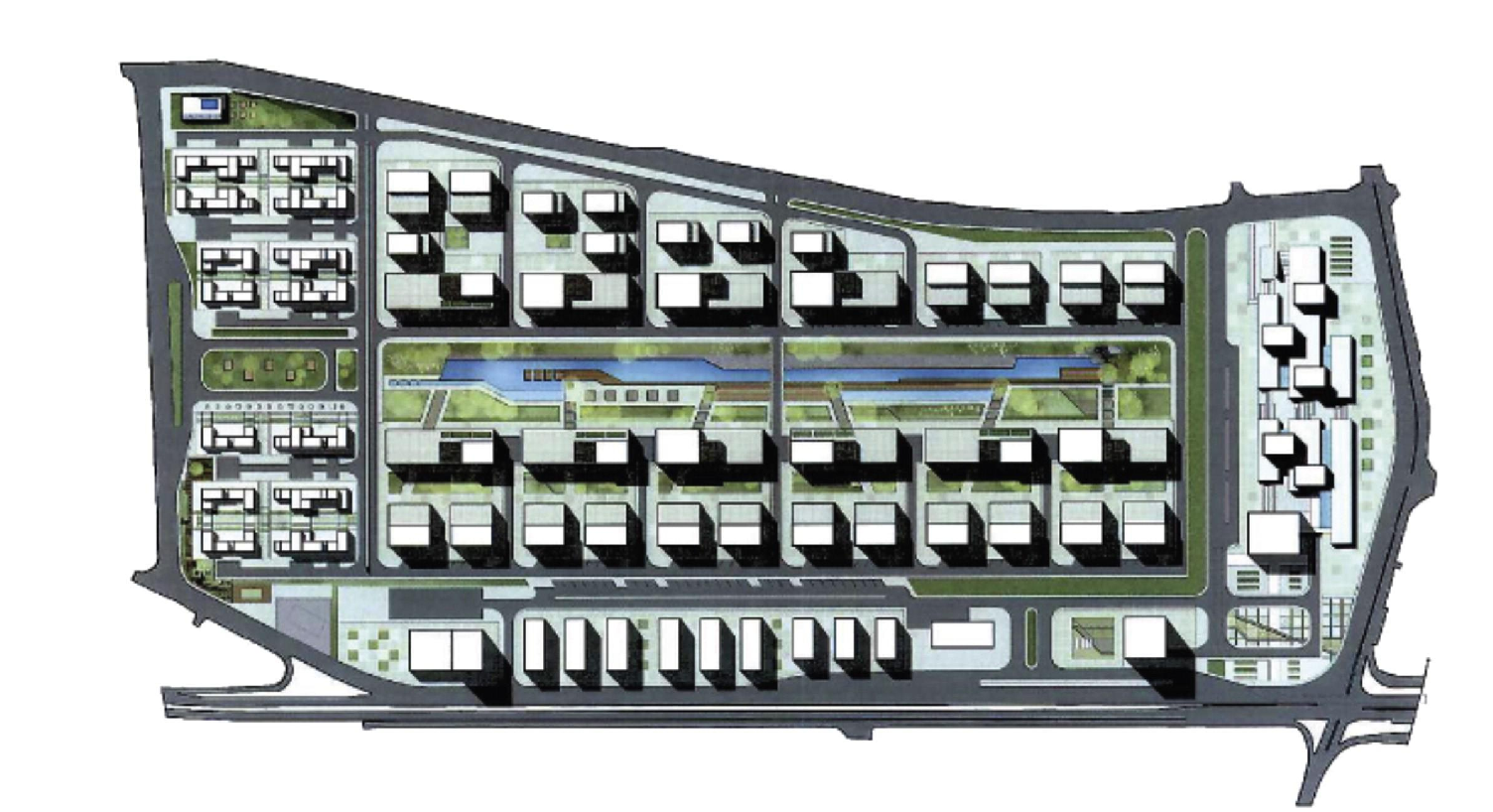

The Village is composed of a variety of residential options, ranging from stand-alone villas to a series of 20 apartment buildings offering 850 units.[6] The Vice Chairman and Chief Executive Officer at KIPCO proclaimed the design imperative of the project:

“Villas at the premium end of the market and the apartments are targeted at young Jordanian families looking for starter homes… the focus of Royal Village is to provide exclusive living with privacy and comfort, within a master-planned environment that is unique, and which will set a benchmark in quality residential accommodation.”[7]

In 2014, I interviewed a special projects planner at GAM and spoke in detail about the various projects throughout Amman that had, prior to the economic crisis, been approved and undertaken, but were also left incomplete. The main cause for the stagnancy of these various projects was, as the planner claimed, problematic site selection. The planner felt that the planning of the Royal Village was especially problematic because it required a lot of changes to the surrounding areas in order to accommodate a project program of its size. In particular, the high-rise apartment structures generated a level of density that would require extensive infrastructure improvements, such as the construction of bridges and tunnels to accommodate increased traffic flow. If left as mid-rise housing, the planner said, the project would have been better planned, and, at a scale more easily built. Finally, it would have been in context, whereas the high-rise component was incommensurate with the surrounding areas, and, in the planner’s personal opinion, ought to have been left out. Soon after construction on the Jordan Gate began, development of the Royal Village was put on hold. As the planner joked in our interview, “what project in Amman isn’t on hold?!”[8]

A central cause for this stagnancy a system of unregulated planning, in which there is no inter-agency cooperation, or, communication. Rather, planning is haphazard, blinded by capital incentive. In an interview with an Amman Institute planner, I was informed that a Vision Document had been conceptualized in 2008, detailing a new developmental hope for Amman. This document attempted to outline a proactive rather than reactive response to planning, but the implementation of the Vision Document, as the planner conveyed, had to be placed on hold soon after its inception. The planner recalled that the document had hardly been completed before the Amman Institute planners were diverted by having to accommodate various high-rise projects set for construction. The planner explained that construction orders and project approvals did not come from the Municipality, rather they came from the court system, and GAM simply had to accommodate.[9]

Royal Village Site Plan. Gross site area is 443, 984 square meters.

The Royal Village was sited in an area that borders the airport road, called Marj Al Hamam. This housing development—with its many high rises—was meant to emulate global modern living. Once again, in pursuit of the modern milieu, all design and planning logic went to the wayside. Ill-sited and ill-planned, the project was doomed to failure, having only succeeded in clearing a previously functioning industrial area and enriching some developers and officials. Haphazard decisions were made, and now all that stands on the site is a withering signpost, advertising a new mode of modern living. These haphazard decisions seemed inevitable, and the planner I interviewed was resigned to their limited ability to genuinely inform planning practice in Amman. These types of decisions further mark a deregulation of planning practice in Amman, and the disempowerment of GAM as a regulating body.

The Limitless Towers

Unlike the Jordan Gate Towers, for which the municipality was all but forced to forfeit public land, the Limitless Project was a pre-approved and pre-zoned project included within the newly completed Metropolitan Growth Plan, which designated new high-rise corridors. GAM posted a call for proposals for the site, encouraging international investors to purchase the land for a high-rise residential development. GAM received several offers and finally accepted the most generous, from Sanaya Real-estate, for a twin towers project designed by JAHN Murphy Architects. The project broke ground in May 2008 and, though designated for completion in 2011, never progressed beyond the excavation stage.

Each tower was designed to be 67 floors (206 m) in height, covering 2.3 acres of land, with a built-up area of 176,000 m2 (1,894,000 square feet). The minimalist and sleek towers pinned between them a swimming pool, suspended 125 m above ground. The sky-bridges below the pool would provide wind-generated power and recycling systems meant to make the entire complex more energy-efficient, estimated to save up to $2 million a year in running costs. The project, valued at 300 million USD, was also programmed to provide 520 residential apartments, including 40 luxury lofts and eight penthouses. At the ground level were two main plazas leading to four floors of commercial space with a total area of 2.47 acres. The Municipality sold the 4.6 acres of State land to Sanaya Real-estate for 5.515 million dinars (approximately 7.278 million USD), with an additional 4 acres of land for a parking garage, sold for 1.2 million dinars (approximately 1.696 million USD), with the stipulation that JAHN Murphy design a public park at the ground level of the parking garage. Located in a natural valley, the project site was chosen at the terminus of two major thoroughfares, an intersection of two newly designated growth corridors that connected East and West Amman, with the newly completed GAM offices to the south.[10]

The Limitless Towers. A rendering of the design, placed in context.

The development site was placed along the built-up corridor so that—even at 206 m in height—the towers would not block the residential landscape along the valley hillside. This siting scheme was, according to a planner at GAM, the result of “a lesson learned from Jordan Gate.”[11] Soon after the sale of the land, GAM issued the proper licenses and permits for the project and excavations began. A GAM planner noted that upon excavation, a high-water table was discovered, the result of a leaking water network that had drained to the low-point in the valley, the Limitless site.[12] Nonetheless, excavation carried on, Sanaya intent on using the water table to its benefit, furthering its energy-efficient goals.

Soon after ground-breaking, the financial crisis of 2008 stalled the project, as Sanaya Real-estate and its primary investor, Dubai World, weathered the turbulent economic climate. In April 2014, GAM approached Dubai World and Sanaya, and, hoping to revitalize the project, offered to defer payment of debt. As the planner said, “even if they just started it a little bit, just to see progress would be good, it would give us hope,” carrying on to wonder aloud, “why does this keep happening to Amman?”[13] The planner then offered the consolation that most people didn’t know about the project, as, unlike the Jordan Gates, Limitless was not on a prominent site, so the project’s failure was likely to be unnoticed by the public. He declared this despite the ten-foot-high fence, adorned with advertisements for the project, that, upon my questioning, he confirmed were still present at the site, six years after ground-breaking. The disregard of the public and the lack of real concern over their notice of the failed project is indicative of larger planning errors, where the public good and public interest are considered rarely, if at all. In the planner’s view, the public lacked the sophistication necessary to ascertain the project’s stagnancy and failure. Toward the end of the interview, the planner explained in a hushed and somber tone that just recently GAM had filled in the massive crater, for public safety. This was done only after two boys had gone to the water-filled crater to swim, and one had drowned. The family of the young boy had sued the development company, but GAM, unwilling to alienate a potential investor, took over and filled the site for public welfare, as if in service of its citizens.

Conclusion

In as much as development projects such as the Limitless Towers and the Royal Village create enclaves of exclusivity, the zones of disinvestment outside of them, so too become enclaves of poverty and deterioration.[14] Further, this form of modernist neoliberal planning enables the construction of mega-projects, on the city periphery, connected by infrastructural networks, only accessible by car for hire, or private automobile. Urban enclaves, or zones of exclusivity, are each connected by highways, or bypasses, that connect one exclusive enclave to the next. Consider the Abdoun Bridge, connecting South Amman to the exclusive shops and restaurants in Abdoun, or the auto centric overpass that shuttles cars into the Abdali project, essentially excluding those who do not have access to a private vehicle.

While these sorts of urban maneuvers seem subtle, perhaps only meant for convenience sake, they nonetheless have a very real socio-economic effect on surrounding areas and communities. The spaces that are bypassed by these motorways so too become enclaves, but they are enclaves of disinvestment, deterioration, and all too often, poverty. As Stephen Graham and Simon Marvin have noted, many infrastructural projects “ostensibly developed to support coherence and urban egalitarianism, have often been appropriated to support fragmentation.”[15]

Despite the upturn in the global economy, the Limitless Towers and the Royal Village remain untouched, stagnant marks on the landscape. The Royal Village, as revealed in my interview in 2014, has no completion date conceptualized, much less targeted. In each of the projects I presented, the built embodiment of neoliberal representation—icon, spectacle, monument—also symbolizes the failure of neoliberalism. Neoliberal urbanism and the projects produced in Amman were intended to be the catalytic converter for change, growth and prosperity, yet they stand in ruin. Neoliberalism is therefore turned on its head, the failure of each of these buildings directly opposing the logic of their inception, directing citizens to question the legitimacy of the State and its governance structures. Private incentive plays a heavy hand in the conception and realization of development, tipping the favor of neoliberal process toward private endeavors. Further—and perhaps most detrimental—is the lack of accountability for administrative decisions made in regard to development in Amman. Lack of regulation allowed both public and private lands to be appropriated for private development without any bureaucratic or financial consequence. The only effect of these projects is the craters and cranes that speckle the city, where detours along city streets attempt to divert drivers away from construction zones, hidden away behind gates adorned with posters portraying the glimmering promise of a modern Amman within.[16] Each failed project is the product of a system of ruination and an expression of a promise that has not been and cannot be kept.

* Eliana Abu-Hamdi, PhD., is currently the Global Architectural History Teaching Collaborative Project Manager at MIT, as well as Adjunct Assistant Professor at Hunter College, in the Department of Political Science, teaching Global Poverty and the Ethics of Development and Cities and Globalization. She is an urbanist, designer, and Middle Eastern/Global South scholar with published articles in the International Journal of Islamic Architecture, Traditional Dwellings and Settlement Review, and Cities, as well as a contributed chapter in an edited volume on Urban Governance in the Middle East from McGill-Queens Press, and another in print, on Social Housing in the Middle East from University of Indiana Press. Her research on architecture and development in Jordan contributes to the debates on the political economy of urbanism in developing cities, thereby establishing a connection between their geopolitical histories and urban present. Eliana received her Ph.D. and Master of Science degrees in Architectural History from UC Berkeley with a designated emphasis in Global Metropolitan Studies. She is an experienced architectural practitioner and educator.

-

References[1] Peck, J. (2004). Geography and public policy: Constructions of neoliberalism. Progress in Human Geography, 28(3), 397.

[2] Hourani, N. (2014). Neoliberal urbanism and the Arab uprisings: A view from Amman. Journal of Urban Affairs, 36(S2), 654.

[3] ibid.

[4] ibid.

[5] Government Official, personal communication, June 4, 2014.

[6] King lays cornerstone for Jordan Gate (2005, May 29). Media and communication directorate Royal Hashemite Court. Retrieved from http://kingabdullah.jo/index.php/en_ US/news/view/id/3309/videoDisplay/1.html

[7] ibid.

[8] Government Official, personal communication, June 4, 2014.

[9] Government Official, personal communication, June 9, 2013.

[10] Greater Amman Municipality (2014). The Jordan Gate Towers: Special Projects Report [PowerPoint slides].

[11] Government Official, personal communication, June 4, 2013.

[12] ibid.

[13] ibid.

[14] Wacquant, L. (2010). Class, Race & Hyperincarceration in Revanchist America. The American Academy of Arts & Sciences, 83.

[15] Graham, S., & Marvin, S. (2001). Splintering urbanism: Networked infrastructures, technological mobilities and the urban condition. London; New York: Routledge. 111.

[16] Parker, C. (2009). Tunnel-bypasses and minarets of capitalism: Amman as neoliberal assemblage. Political Geography, 28, 112.